Growing up in a conservative Mormon family, Samantha Allen wasn’t taught that she was assigned male at birth, but that it was decided divinely before birth. So when she was drawn to her sister’s clothes more than her own and felt more female than male, she was a bit confused.

Allen tried to suppress these feelings and live life as a good Mormon kid, and she even started college at the Mormon-owned Brigham Young University in Utah. But her gender dysphoria persisted, so she ended up leaving the church and transferring across the country to Rutgers University. One of Allen’s majors in undergrad was in women’s studies, which fascinated her, and she went on to obtain a PhD. in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Emory University in Georgia. She used academics to explore her gender identity, and through the help of a gay man and mentor who ran the LGBT student center at Emory, Allen began the process of coming out when she was 24.

Soon after, in 2013, Allen earned a fellowship to study at the famed Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction at Indiana University in Bloomington. During her time there, she had a chance encounter with another student, Corey, who supported Allen through the early stages of her transition and later became her wife.

While in grad school, Allen began freelance writing in her areas of study to help pay the bills. Her original career path was to be a professor, but she found herself becoming a journalist instead, and a gifted one at that. Allen’s writing has now graced the pages of both scholarly journals and national news outlets, and she’s won a GLAAD award (and been nominated a second time) for her LGBTQ-related reporting. She also wrote a short memoir, Love & Estrogen, recounting her love story with her wife. Most recently, she was a staff writer for The Daily Beast, where she covered primarily LGBTQ issues. Toward the end of her tenure, she did an incredible job reporting on all aspects of the trans military ban (she even interviewed me for a story on it!).

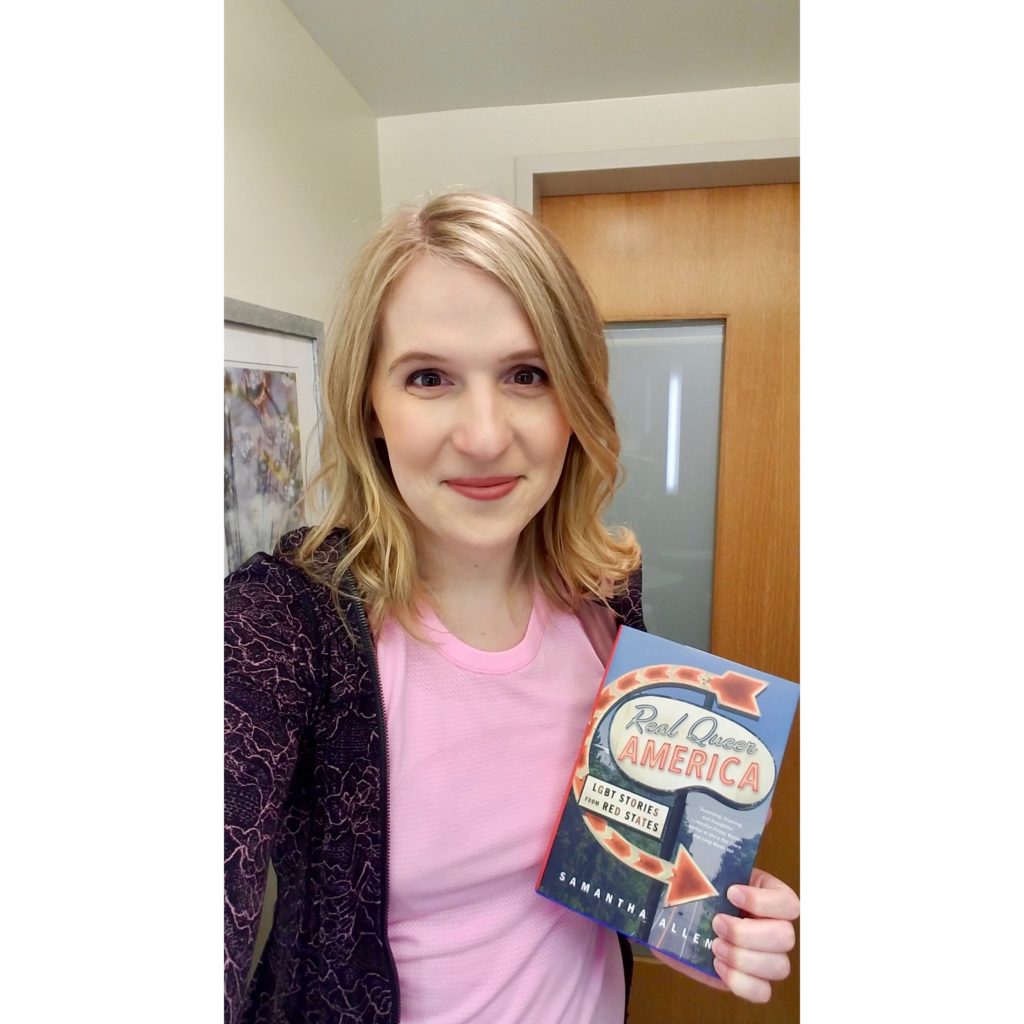

Having lived in several red states, Allen knew that queer communities existed everywhere — not just the coasts. And unlike many other journalists, she wasn’t shocked when Trump won. After his victory, when everyone else was trying to figure out how he managed to win, Allen, who found solace in long drives, decided to instead go on a six-week road trip across the country. She was determined to understand what life was like for queer communities in these red states and why people chose to live there. Earlier this year, her powerful stories from that journey were published in her book, Real Queer America: LGBT Stories from Red States. (Editor’s note: I read it and am obsessed with it; please get your copy ASAP.) Throughout the book, she also weaves in reflections from her own personal journey as a trans woman.

On this adventure, Allen found that queer people are not just surviving, but thriving in unexpected places, and that queer communities in red states are often closer, more welcoming, and more engaged since they usually have no choice but to band together and fight for their rights. Queer folks in liberal areas typically have the privilege of living more freely and openly, she explains, but it often results in a less engaged, more complacent and disconnected LGBTQ community.

After spending most of her adult years in red states, Allen recently relocated with her wife to the Seattle area, but her passion for red states lives on. This is Allen’s story of coming out as transgender, finding a calling for writing about the LGBTQ community, and traveling across the country to learn and share the stories of queer Americans choosing to live in red states.

Profiles in Pride: I know you discuss this at length in your book, but for those who haven’t read it yet, when did you realize you were trans, and what was coming out as transgender like for you?

Samantha Allen: My earliest memories were stealing clothes from my sister’s dresser. This was 1988 or 1989, or whenever I could walk and open a drawer. I obviously didn’t know human language, let alone the word “transgender.” So my childhood was a really confusing time, especially growing up in a Mormon household, where at some point me stealing my sister’s clothes went from being some funny cute thing I did to being a reason to be ashamed.

Kids get that message so early on, so I started hiding that habit at a pretty young age. Like a lot of folks, when I came out as transgender, it surprised even some people in my family; my parents expressed some kind of shock. I was like, “Don’t you remember how I used to steal [my older sister’s] clothes?” I guess a lot of parents just thought their child grew out of that phase. “No, I kept doing it, I just knew I had to hide it from you!”

They were feelings that I grappled with through my teenage years. At some point I found the word “crossdresser” and that made some sort of sense to me, even if it didn’t feel super accurate. But I was deeply ashamed of it. I’d been raised in a religion that taught me our gender is assigned to us before we’re even born, in the premortal realm. It’s a teaching of Mormonism; talk about gender assigned at birth — it’s assigned in the premortal existence!

When I was 17, I had this moment of deep shame around crossdressing and around dating people. I turned full-force into Mormonism. I was like, I’m gonna follow all the rules and put this behind me and be a young Mormon man and go on a mission and all of that. That lasted from age 17 to 20. I came home from my mission early on medical leave and I was at BYU in Utah, a church-owned university.

I just knew I couldn’t run from it anymore, so I started exploring my gender identity again at BYU in my early twenties. I think by that point, around 2007 or 2008, I’d heard the word “transgender,” but I knew nothing. I didn’t know that you could take pills that literally reshape your body and your brain chemistry! My impression of what being transgender meant at that point was that you go get a sex change at the hospital, or something like that, just based off really trashy popular depictions of what it meant.

Then I transferred away from BYU, I left the church, I started taking gender studies classes at Rutgers, and I started learning more about LGBT community. Eventually in grad school, I ended up in a gender studies PhD program in Atlanta, and that’s where I met other trans folks for the first time and where I finally came out myself. I was 24.

PIP: With all of these degrees in gender and sexuality and a fellowship at The Kinsey Institute, were you drawn to studying it because of your own experience?

SA: Yeah, I was definitely working out personal issues through academic study. It was almost easier to grapple with it in the abstract than it was to admit to myself that I had to change. Like a lot of trans folks do, I’d read about trans women, and I’d be like, “Oh, that’s cool, but that’s not me.” I’d try to reassure myself or something. Yet, of course it was me — it had been me my whole life. It was an interesting and indirect way to arrive at a deeply personal understanding.

PIP: What did you plan to do with all of your studies after school?

SA: I was going to teach, I think. I just got really interested in it. I double-majored in undergrad in linguistics and women’s studies, and I was originally planning to pursue linguistics in grad school.

Women’s studies just kind of took over, just because gender is, along with race and class I think, is one of the primary ways we organize human society — yet people laugh at it as though it’s unworthy of being studied in a university setting. It’s like, oh this huge rubric that defines and shapes so many of our experiences? How can you not examine it? How can you not find it amazing?

PIP: How did you end up pursuing journalism instead?

SA: While I was in grad school, I started freelance writing on the side to bring in some extra money. Graduate student stipends are not exactly large allowances, so I needed some spare change, and I started freelance writing. I enjoyed the immediacy of you write something, someone reads it, it makes a connection with them. Whereas in the academic world, that process moves so slowly. My first journal article, between the time I wrote it and the time it came out, it took a year and a half or more.

PIP: I know a lot of what you write on is about the LGBTQ community and sexuality — was it your intention to become a journalist in the areas you previously studied?

SA: Yeah, I did mostly personal writing at the start, and that kind of slowly morphed in journalism. I think writing for me has always been the common thread. A lot of folks do journalism because it’s a way to write. I’m not saying that I don’t love sharing other people’s stories and the power of good storytelling and sharing accurate information, but I think on a personal career level I’ve always just loved putting sentences together. There are very few ways you can do that and make a living!

PIP: While you were at the Daily Beast, you covered the trans military ban often — was that your own initiative to shine a light on that and cover it?

SA: Yes, I was on the war path of like, “We need to cover this from every single angle possible.” I wanted to know about how the April 12 deadline was affecting trans service members. I wanted to know how folks who had been grandfathered in under the old policy were going to feel after the door closed behind them. I wanted to know personally how friends and family members and spouses and parents were feeling and dealing with the anxiety of the last few years.

In the build-up to the ban, I was very much pitching articles all the time about every possible facet of the ban. To be frank, and maybe you can relate to this, I found it troublingly and disconcertingly hard to get readers to care about it.

PIP: Yes, it seems like people often don’t care about issues until it personally affects them or someone they care about.

SA: Yep, I was writing these stories and was being emotionally impacted by writing them, and the personal stories I was including in the articles I thought were really powerful and compelling. And yet, and I think this ties in a broader fear of trans issues in the US, fewer people have connections to trans people than they do to cisgender lesbian and gay folks. I just worry sometimes that there’s an empathy gap that can be really hard for the trans community, myself included, to overcome.

PIP: Absolutely. So what gave you the idea of taking a road trip across the country and writing Real Queer America: LGBT Stories from Red States to document it?

SA: I’ve encountered a dismissive attitude toward “flyover country,” in the queer community especially. I know that comes from a historical place of a lot of LGBTQ people moving to coastal safe havens like San Francisco or New York, yet I think it ignores the fact that many, many, many LGBT people live, have stayed in, or have moved back to more conservative parts of the United States. Nearly 4 million LGBT adults live in the South alone; I think it’s the largest out of any region in the country. What gave me the motivation first and foremost was just to say LGBTQ people are everywhere, which I think given our media depictions of LGBTQ life is still something that needs saying, even as it seems so obvious.

More specifically, I was writing the book in 2017 in this post-election moment when a lot of journalists and writers were turning to the middle of the country for some sort of understanding of “how did Trump happen?” Having lived in Georgia and Florida between 2010 and 2017, I knew how Trump had happened — that wasn’t a mystery to me. I had a sick feeling in my stomach when Trump won, but I didn’t feel blindsided by it.

I wanted to write a book that was like, everyone else seems really interested in the people in the middle of the country who voted for Trump — I’m interested in LGBT folks and their allies who have lived here and who will one day I think overcome the prejudice that fuels the Trump movement, even if it’s not happening as quickly as people on the coasts would want it happen.

PIP: You open up the book by talking so beautifully about the definition of queerness. Can you explain in short what it means to you?

SA: When I was in graduate school learning the etymology of the word “queer,” Eve Sedgwick was a revelation for me, both intellectually and personally, so it was definitely something I wanted to include right upfront in the book.

To me, queerness is a way, not of denying labels altogether, because they have their utility, but evading them. I think long before I had any vocabulary to describe who I was or what I was, I knew that there was something weird about me. It’s not a coincidence that queer is a synonym for weird.

I had these very loosely defined feelings and thoughts and conceptions about myself that I had no language for. I think the utility of queer is in its ability to take you back to that place with more confidence to say, “Yes, I’m a woman, yes, I’m a trans woman,” and I identify with those labels and they’re really personally meaningful to me, but queerness transcends those identities, and it’s a refusal to be boxed in.

At its most basic, it’s a way of saying, “I’m not straight and you really don’t need to know anything else.” It can function really usefully in social settings in that way, but I think it’s also deeper than that. It’s about an embrace of the weird.

PIP: I love that. What surprised you the most on your journey throughout red states?

SA: I think I was most surprised by going back to Provo, Utah, because it was a place where I’d felt so much shame and fear when I was still in the closet. To go back there 10 years later and find an LGBT youth center across the street from the Mormon temple, full of trans and gender non-conforming kids playing card games and listening to music and laughing and being carefree, it was surreal. I knew in advance going back to Provo that I was going to this LGBT center and interview people, I didn’t really know what to expect. Just the second I walked into the doors of Encircle, I couldn’t believe it. That was the most surprising thing to me.

I think the most eye-opening, most interesting place I went to, or the one that made the biggest impression on me, was the Rio Grande Valley in Texas. Just because it’s a part of the country that is at the nexus of so much of American politics, and yet so few people go there unless they live there. There’s a bit of eco-tourism, but it seems like not much else in terms of outside interest in the Rio Grande Valley, and yet millions of people live in the Rio Grande Valley, and it’s a hugely important cultural space in the United States. It was really interesting to be there in this place that’s technically blue, but can feel fairly conservative around issues of sexuality and gender. A lot of folks on the ground are trying to make the RGV a more queer-friendly place to be.

PIP: I loved your conclusion that queer communities are not only in red states you wouldn’t expect, but also tend to be closer and more engaged in those places since they have to band together and fight for rights in a way LGBTQ folks on the coasts don’t have to do. I fully relate to that since in our queer communities here in Texas are tight-knit and very politically engaged.

SA: Yes, LGBTQ Texans are a fearsome brood! I’ve never, ever been in a room as loud as the Capitol rotunda when LGBTQ folks were in there protesting legislation, and they do that every time! I’ve been to sporting events in Seattle, a place renowned for loud fans, and they aren’t as loud as that rotunda was!

I think it comes from knowing what the stakes are. When every year you have people who have literally made it their jobs to try to legalize discrimination against you or putting penalties on you for simply being alive or live a public life, you have to show up, and you have to shout.

That’s been my experience personally, and while writing the book. The LGBTQ folks that I meet in red states, there’s an awareness of like, yes this is hard, yes this is really challenging, but there’s also a resilience that I think can emerge from that, and I encountered that over and over again, not just in Texas, but across the country as well.

PIP: Yes, and I loved the point you made in the book about how Prop 8 passed in California because people in the LGBTQ community had become apathetic and didn’t vote. They just assumed it would be defeated since it was California.

SA: Yes; a sociologist I interviewed a while ago did a social survey in Massachusetts where same-sex marriage was legalized first. When that happens, when marriage equality gets out ahead of a lot of the other issues facing the entire LGBTQ community, I think it’s led to a fracturing of the community, a certain complacency. Also just a feeling of “we’ve arrived, we can just blend in.” What happens, when you get that kind of attitude, bisexual and trans folks get left behind. We see that sometimes in blue states.

You know, I’m making a thesis and an argument in the book. I want to of course say there are amazing blue state activists and apathetic red state LGBT activists, but in my personal experience, the places where I’ve felt the community most engaged and politically active have been in those most conservative parts of the country.

When I hang out with gay people in West Hollywood, I totally get it if someone’s like, “I just don’t want to wave the flag right now. I just want to live a life.” Because straight people get to do that, and there’s no reason why LGBT folks shouldn’t be able to do that. And yet, there’s still so much work left to be done, and someone has to do it.

PIP: Definitely. Now tell us a little about your wife, Corey!

SA: We met in the elevator of the Kinsey Institute in Bloomington, Indiana — a very queer rom com, but it’s my life! It was the summer of 2013; I was there doing research for my dissertation, and Corey was finishing up her undergraduate thesis. We saw each other from across the room, got into the elevator at the same time,and I nervously said hello to her, which turned into dinner, which turned into us not spending a night apart for the next month.

Corey is magnetic, smart, funny, and silly when she wants to be, and when she opens up to you. Corey really held my hand through some of the early stages of gender transition; I’d just barely started hormones a few months prior to meeting her.

I still felt very awkward, I still didn’t feel super confident in myself. It didn’t occur to me that this striking young woman who was attracted to other women would be attracted to me. I wasn’t at a place of self-acceptance or self-love where that even registered as a possibility for me. So to feel her want to be around me, and to want to be with me romantically, was tremendously flattering and also hugely validating.

Going through that journey with someone is very intense and binds you together. Corey was there for my surgery too, and I leaned on her a lot in those early years of it, and less so now, but it was an experience that really bound us together.

PIP: Before we go, is there anything else you want to share?

SA: I think “love is love” was such an effective slogan for marriage equality because of the universality of love and how much people can relate to love. I think one of the things anti-LGBTQ groups did successfully was they made trans stuff synonymous with bathrooms and they made that stick so hard to the point where we have to really fight to overcome it.

I wrote a little memoir called Love & Estrogen about our love story. One of the reasons I wrote that is I think we need to have more trans love stories. Trans people need to own love too, politically and personally! Trans people are loved, and they love people. Maybe that’s the way to fix the empathy gap, to point that out.

PIP: Absolutely! As a partner of a trans person, I totally agree, though sometimes it’s hard for me to figure out how to verbalize it without it sounding like a fetishization of a trans person.

SA: It was interesting for me, because one of the things that was so great about being with Corey is she saw me as a woman first and trans second. That was so important to me, especially at the start of the relationship. As we’ve gotten further in our relationship, we’ve been able to talk about ways in which Corey — it’s not that she fetishizes my transness, so much as she can see its impact on our partnership in ways that she appreciates, and its impact on me personality.

It makes me think about Laverne Cox’s “trans is beautiful” slogan, where we’re not measuring the beauty of transness by how well it can imitate being cis, but in its own right — that trans, whether that’s meant to refer to physical attributes or psychological ones, is beautiful in and itself. I think that’s really powerful.

Learn more about Samantha on her website and keep up with her on her Facebook page.