Ji Strangeway’s immediate family lived in diaspora in Laos during the Vietnam War. They escaped a violent country and immigrated to America, only to be met with prejudice in Denver, Colorado. Torn between her Vietnamese and American identity, she also struggled with growing up gay. Her traumatic childhood left her with a soft spot for LGBTQ youth who don’t fit in or who experience bullying.

As soon as she was old enough, she moved to New York and pursued filmmaking. She currently lives in Los Angeles, working as a creative on numerous fronts. She is a screenwriter, film director, novelist, and poet.

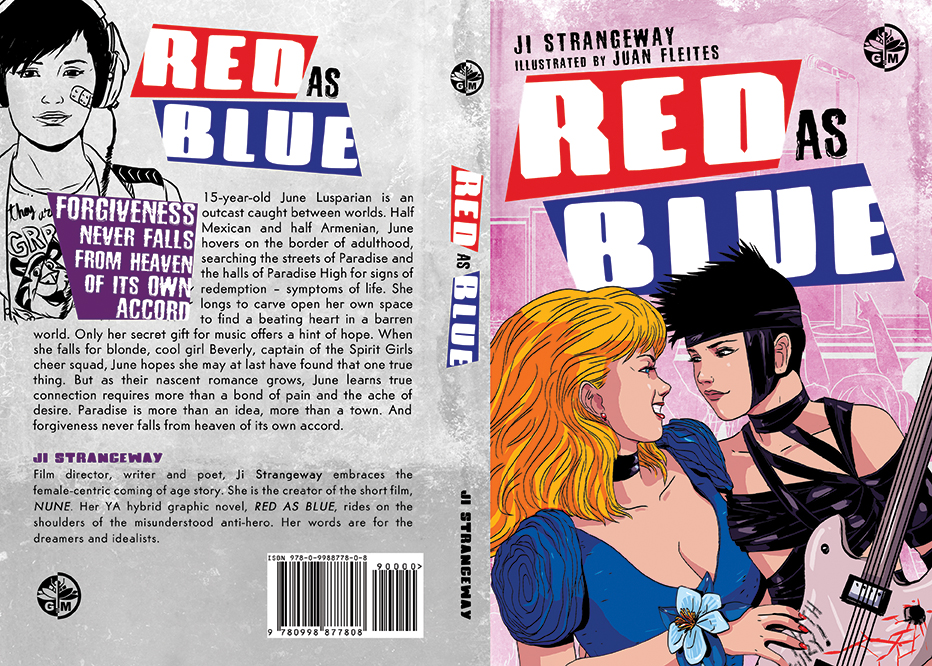

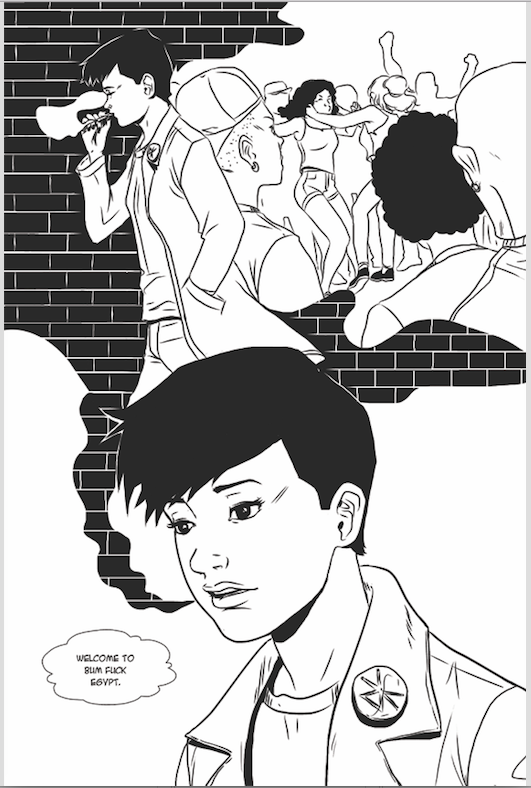

Strangeway has written a hybrid graphic novel called Red as Blue, which has a one-of-a-kind format that’s something like a comic book, screenplay, and novel all mashed into one. It’s an LGBTQ coming-of-age story that releases in spring of 2018. She has also written and directed the short film Nune (2015), which is an adaptation of Red as Blue. It’s a female-focused coming-of-age story about a bullied high school girl who finds unexpected love with a popular cheerleader.

Here is Strangeway’s story of overcoming a challenging childhood, creating a film with a powerful message, developing a graphic novel unlike anything that’s ever been done before, and striving to give bullied LGBTQ youth hope.

Profiles in Pride: Can you first tell us a little about your background?

Ji Strangeway: I’m actually Vietnamese, but I was born in Laos and immigrated here from Laos. I grew up in Colorado, which was a really awful experience. As soon as I was old enough, I ran off to New York and decided that I wanted to pursue filmmaking. Basically, I never wanted to return to Colorado when I left.

It was really eye-opening coming to New York, because in Colorado, at the time, we were the first Vietnamese immigrants there, and everyone was just like, “Go back to your country, you don’t belong here.” It was awful, because we’d been displaced already in going through a violent war, and being in this so-called beautiful America, the Promised Land and all that, but it ended up being the worst nightmare of your life, because in your country, nobody treated you that badly.

I had a combination of terrible racism throughout my whole childhood up through high school, on top of the sexual identity thing. It was a massive double whammy. I basically turned extremely suicidal by the time I was 15, and it was just a very dark, dark time.

I think it’s been an amazing journey, because coming back to Denver now, you would never think, as a tourist anyway, that a place as beautiful as it is could be anything like that. It was extremely oppressive, and I do feel a lot of that old consciousness there, and it is a really low consciousness. And I think it comes from the fundamentalist Christian thing. Colorado Springs, I think, is the mecca headquarters of evangelical churches.

I’m releasing a graphic novel called Red as Blue. A lot of it is based on the culture that I grew up in and the darkness and pain of it. It is a work of fiction; it’s not autobiographical. But the reason I mention it is because when I was doing the art with the illustrator, there’s a scene in there where I wanted to have a high school image of the ideal high school where all this violent stuff occurred. I said, “You know what, I’m just going to Google my old public school.”

There’s a historical theme in my novel that is my comment on the Columbine shooting and why I believe it happened. Despite the fact that this is a love story, the bullying in my story escalates in the backdrop of violence. So when I Googled my school, I found this aerial image of the school and I couldn’t fuckin’ believe it. The school was shaped like a cross. A perfectly shaped large crucifix that houses like 3,000 students. I’m thinking to myself, “Oh my god, all this time I’m entering the symbol of a crucifix in my youth. Wow, that’s crazy.”

From a symbolic perspective, that image pretty much says everything about what I believe to be the cause of so much of the problems of growing up in a place like that. It just breeds so much hatred. It’s such a trite thing to blame religion, which I’m not really doing. I’m not blaming religion, I’m kind of just saying what the cause is. It’s different to blame someone in a blanket way. It’s another thing to say, “I know what it’s like to go to a school shaped like a cross.”

PIP: Tell us about your short film Nune, which you wrote and directed a few years ago. What compelled you to make it?

JS: It’s actually a modern version of the novel that I’m writing, which is kind of strange. It’s an adaptation of a book that hasn’t been released. I would have done the short film based in the 1980s, but for budget reasons, I couldn’t do that.

It was a very fascinating experience, because it was essentially the same story, but flash forward from 1984 to 2014 or 2015 when the film was being made. I was like, “Wow, how do you rewrite this? How do you make bullying relevant?” Because in 1984 and before that, in terms of writing, there’s so much more at stake. And I’m like, “How are those stakes relevant today?”

Because today, nobody really seems to have it as hard. I had to change the story a little bit, and I was trying to make it more about transcendental love. How love transcends everything. The fact that this girl, Nune, is hated on at her school and bullied, and the fact that the most popular girl in school falls for her. How do we transcend the barriers that keep us from coming together?

I also thought it was really hard to make a film where the two girls looked straight. Because in the past, you had a very kind of butch/femme thing going on. I think a lot of that was just societal and kind of survival, because how do you show you’re gay in the past? You kind of have to look kind of androgynous. Not that we have a strategy for it, but that was just part of the culture. So it was challenging in a good way to show two girls who are very straight looking, in my opinion anyway, be gay.

What’s cool about Nune, the film, is I loved the modern take on Red as Blue, because it really is about where our consciousness is now about the whole “love is love” thing. It taps into the idea that love is love, and you don’t have to look gay or straight, you don’t have to be a stereotype of it.

That’s actually why I love the cheerleader theme. My friends think I’m weird, because I know in the back of their minds they think I have a secret thing for cheerleaders. Because I’ve made a film about a cheerleader, my book is about a cheerleader, I was not a cheerleader, and I did not have cheerleader friends, I had to do a lot of homework. So people think I have a cheerleader fetish, but I don’t!

I love the cheerleader theme because for me, it’s a theme about redemption. And I think a theme of redemption for a lot of people. Because as far as we’ve come societally with this whole idea of coming out and not having to look gay or straight, and all this paring down the stereotypes, to be perfectly honest, you don’t know a lot about gay cheerleader unless it’s porn!

There are probably a ton of gay cheerleaders who are still struggling with this. It’s not like I’m out on a mission to save cheerleaders. But it really brings into question, have we really gone that far?

The reason I’m obsessed with the whole cheerleader thing is not the cheerleading itself, but because of my belief in idealism. Idealism means taking the most cherished thing America loves, you know, the blonde, blue-eyed, busty, popular, girl-next-door cheerleader, you name it, and reshaping that ideal. In my experience as teenager, this was not given to me. It was only given to 1) white people, 2) men, and good looking men, straight people.

And it’s like, what if I like that? Well, I can’t get that. It kind of sends a message to me that I don’t deserve the most cherished ideal thing that everybody wants. And that’s the driving force behind Red as Blue and that’s the driving force behind Nune. That’s why there’s the cheerleader, and that’s the only reason why there is a cheerleader.

PIP: When does Red as Blue come out?

JS: The book is coming out on May 15, 2018. The pre-order for that will come out I believe on March 27, 2018. It’s going to be in ebook and paperback. The paperback I must say is a lot cooler. I know everybody loves ebooks, but it’s a graphic novel hybrid, and the format of it is very visual. The layout of the words is visual in and of itself.

PIP: The format itself is like nothing I’ve ever seen before. What was your inspiration for the style and format?

JS: I wrote it that way because I’ve never read a book that I liked to read, because it was never written the way want to read. Even though I’m pretty well read, I’ve always hated reading. It’s just a mechanical issue. I don’t like the idea of opening a book and reading 100,00 to 300,000 words. It doesn’t make any sense to me. I shouldn’t have to work that hard! I mean, that’s why people love movies! When you watch a movie, it’s more of a feeling thing, it’s visceral, it’s visual.

I wanted to take the best out of everything that I like from all the formats of things I’ve read, whether it’s novels or screenplays or comics. I kept all the elements that worked and got rid of everything I felt wasn’t useful.

For instance, I took out all the identifiers in the dialogue. The thing that I find hard to write as an author and also as a reader, is when people have to write “she said, he said, she replied, or he explained.” Why? What’s the function of that? That’s just an example. And I threw it out.

So in my book, it’s a very immediate feeling, where you see the character’s name like a screenplay and they talk, and I feel like you’re just inside their voice and it goes very quickly. The conversation just flows. I figured if I like to read it that way, there’s probably a ton of people that like it too. I also think it has to do a lot with maybe my brain is wired more similar to millennials; supposedly they have ADD, or that’s what people think anyway.

But I’m not so sure if it’s ADD; I really think that their brains are wired to chunk information and to get things very quickly in a snapshot. They don’t need to look at 300,000 words or even a page to understand. They’re very smart. They don’t need to read a whole paragraph on something describing a room. What is the function of that? I don’t want to sound like an asshole but I hate reading things like that. When I describe stuff in Red as Blue it’s because it has a purpose and I need you to know the details.

PIP: It reads a little like a screenplay — was that part of your inspiration?

JS: I write screenplays too, so I think the format is inspired from that, but only in the sense that there are certain things in screenplays that work, but other things are completely useless, too. Screenplays are great in moving you around very quickly into action, but most of it is written for budget, and that’s why it moves the way it does.

The thing I don’t like about screenplays is because it’s written for budget; it never really allows the writer to fall in love with words. I think being a poet too, you have a romance with words, it’s everything. To not have that freedom is kind of like sex versus lovemaking. Screenplays are so mechanical, they’re blueprinty. They’re cold. Nobody reads a screenplay for fun because they aren’t meant to be enjoyed. They’re meant to figure out how much you’ll pay per page to shoot that scene and what it’s gonna cost per day.

PIP: That’s fascinating. Now, to tie it all together, what are you hoping people will get out of your film and book? What do you want people to feel or experience from your stories about LGBTQ heroes?

JS: I know this sounds really cliche, but when I think about my audience, I think about that 15-year-old girl that was me. I know that the 15-year-old girl that is me is always there somewhere in the world, that are having these issues, and they never go away. We think that they’re modern issues, but you can go back as far as you can, and you’ll see that for every generation in society, everyone is always damning the 15-year-old, or the youth.

I find it shocking that people who are my age end up saying the same thing that their parents said and the adults said before them. “The kids today, the millennials today, they don’t pay attention! They don’t give a shit about anything!” Well, they said that about my generation. They said that about the hippie generation. They said it about the James Dean generation. They said that about all the generations before. So what the fuck?

I’m speaking to that lonely lonely girl, or boy, or whoever, who is always going through this whole existential crisis between who they are and what society and their parents and everybody else wants them to be. Unfortunately, so many people want to kill your identity and your potential. And I don’t know why the world has to be that cruel.

If anything, I just want my stories to give people hope. In my stories, the love my characters find is often hard to achieve or defies the myths or social conditioning that tells you you can’t obtain that. I’d like to send the message that you can achieve your ideal, and if you can’t or if this world is too small for you, then you have to create that world. I find that very inspiring. So I’m creating that world for other people and I’m creating that world for myself.

Learn more about Ji and her work on her website, JiStrangeway.com.