Amber Leventry has always been good at keeping secrets. They were molested by a female family member for around a decade, but shame and fear kept Leventry from saying anything until they were 16. They also always had a feeling something was different about them, and when they realized they were gay, they knew that their religious home in Western Pennsylvania wasn’t a safe space to come out.

Once in college and away from home, they felt safer to come out; they also began to deal with some of the trauma of childhood abuse. Over time, Leventry, who had always presented as masculine, began to notice they didn’t quite feel male or female. Then, when Leventry and their partner had their first child, old memories of sexual abuse surfaced. Leventry’s drinking and gender discomfort increased around the same time, but they were skilled at hiding both.

A few years later, Leventry and their partner had twins who were assigned male at birth. As soon as they could talk, one of the twins made it clear she is a girl. Leventry and their partner fully supported the child, and as they began to start advocating for her, Leventry realized it was also time to acknowledge their problem with alcohol and get sober so they could be a better parent. They also realized it was time to fully tackle their trauma and gender identity.

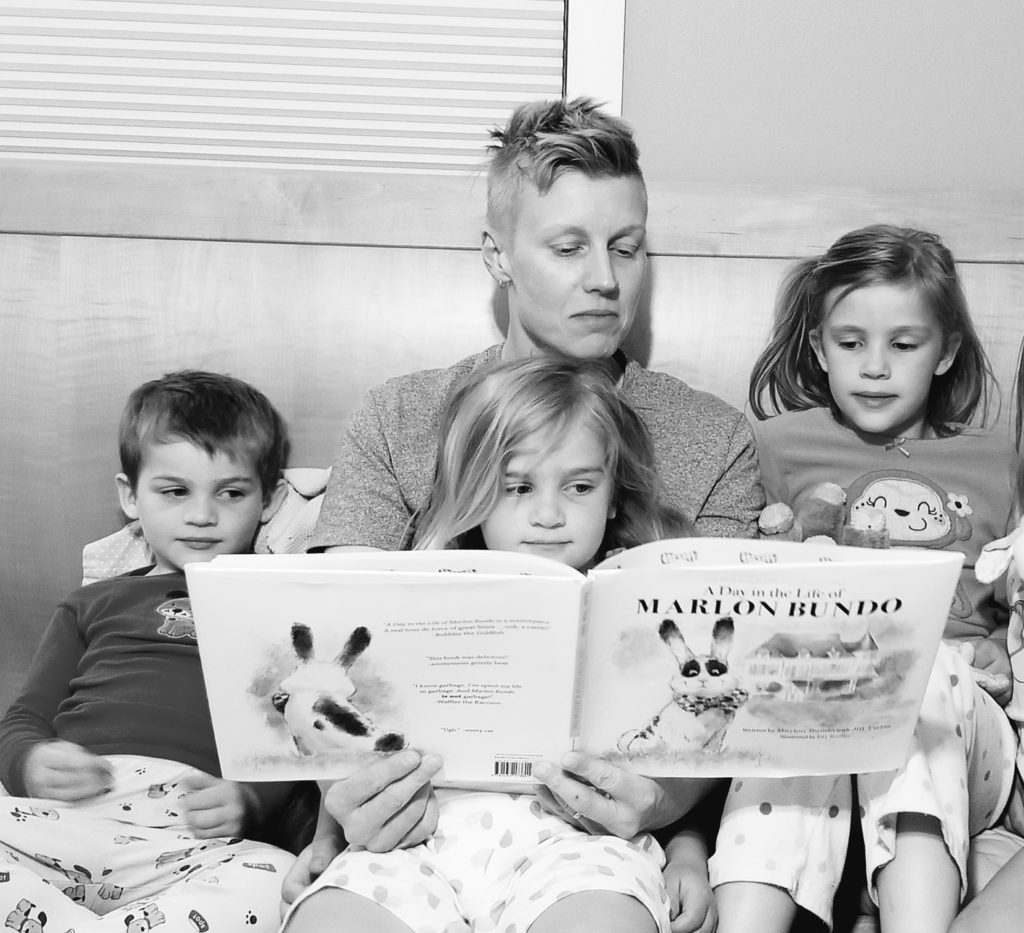

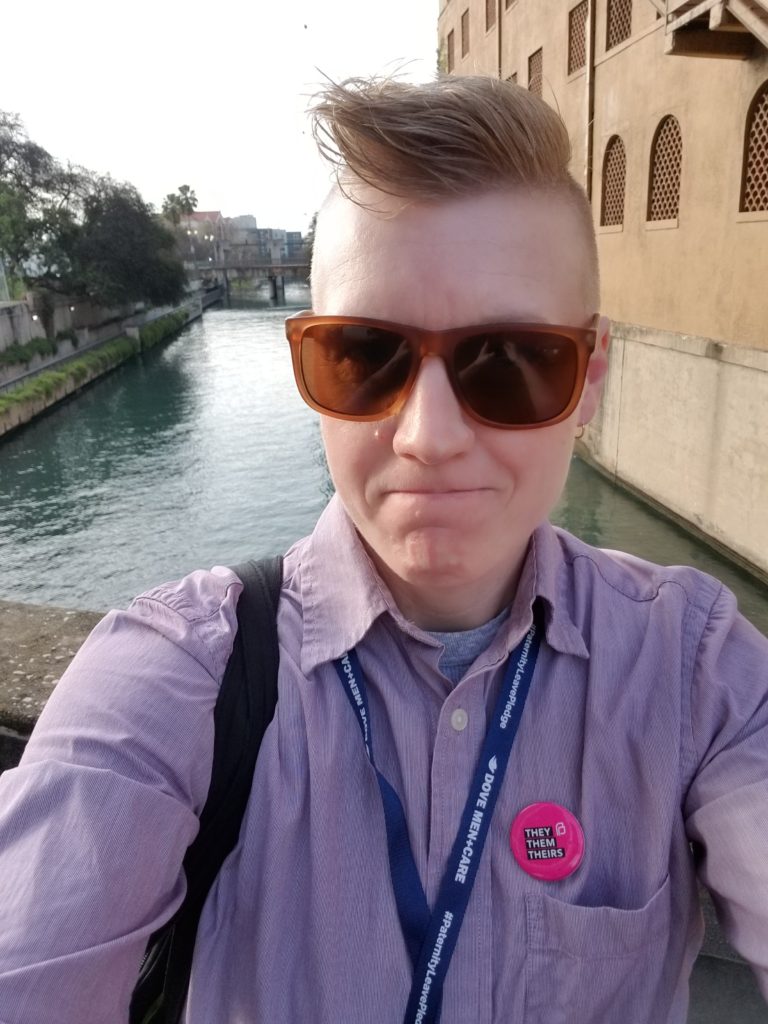

Leventry has been writing for various websites about their experiences as a queer parent, a parent of a trans child, and now about their own gender and addiction issues. The 39-year-old is a full-time freelance writer living in Burlington, Vermont. Through advocating for their kid, they also began a career as an activist, holding events, facilitating trainings, and giving speeches to help the world better understand gender and inclusivity. As they have done this work, they’ve also worked on themselves. Leventry eventually came to the realization they were non-binary, and about seven months ago, adopted they/them pronouns. This has negatively impacted some of their relationships, but finally living authentically has helped them beyond measure.

This is Leventry’s story of overcoming abuse and addiction, coming to terms with their gender identity, being non-binary, and becoming an advocate for their transgender child.

Profiles in Pride: What was your journey to understanding your identity?

Amber Leventry: It’s been a long, long process. I knew from a very young age that my heart loved differently and the feelings I had were probably different from other kids. I knew when I was five that I had a giant crush on a female student teacher in kindergarten when she gave me a Snoopy sticker!

All my stuff is very jumbled in that I was also sexually abused by a female relative from when I was in diapers until I was about 12. That on top of living in a physically abusive house, and — I didn’t know it at the time — a poor house. Because when you’re poor, you don’t know until you’re older. I knew we struggled for money, but I didn’t know how bad it was. So I had all these things floating around me.

I’ve always been very thankful for this inner voice, this kind of a guide I have in me. I knew something was telling me that I was different. Also, from a pretty early age I felt like I wasn’t just female, so I embraced the fact as I got a little older. I was very athletic, so I took the tomboy label and made it OK to be in sports and present in athletic clothes with a more masculine-type appearance. I was like the rough-and-tumble athlete.

Plus, it was the ‘80s and ‘90s, and everyone wore baggy clothes. In the ‘90s, thankfully we had flannel and Nirvana, and everyone looked like a lesbian! It was in fashion to kind of present more masculine or not as girly. I lived in a time where it was OK to do those things even though my mother insisted we shop for female clothes; that was always a struggle. I could never fully express myself the way I wanted to, but I also grew up in a home where religion was really important, so I also knew from a very young age that it wasn’t OK to be gay.

Part of it was we didn’t talk about it, so the silence was deafening, but also any comments around being gay were not positive. It’s interesting how when you are different or queer, or you know you’re going to eventually identify as the gender that you weren’t assigned, you kind of just know. It’s amazing what your spidey sense tunes into, and you know to be quiet or you know, hey, this is a person I can share with. I knew while living in my hometown and at home that I couldn’t share this information.

So I just struggled. I had severe depression as a teenager; I was suicidal and I was not well. I still struggle with mental wellness. I was a perfectionist, which is also damaging, but it got me the grades and credentials I needed. I had the tenacity to get out of my living situation and go to college.

PIP: When did you start coming out?

AL: I finally came out to a few friends as gay when I was a junior or senior in high school, and that was OK for some people. I told a few people I was sexually abused, including my mom and some friends, and that wasn’t received well. I either wasn’t believed, or they said, “Oh, but she’s your relative so it’s not a big deal and you still have to be nice to her at Thanksgiving.”

I wasn’t really validated. It was never allowed to be about me, because there was abuse and grossness in my family. It was like, “Now you’re one of us, welcome to the club, get over it, kid.” On the surface, I was a straight-A student and a great athlete. I went off to Penn State and paid my way through school since my family didn’t have any money to contribute to that.

Also, when I was young, I felt like I was missing a penis. I didn’t really experience body dysphoria at that point, I think since I was an athlete and was physically fit. However, I felt like things were missing more than I didn’t like the things I had, but I just kind of ignored it and didn’t know what it meant.

At college, I was psyched to be out, so I slowly started to come out as gay. I definitely presented myself as masculine. I went through the whole process of cutting my hair, going from a pixie cut to a shaved head — all the transformations that I went through to be able to express myself in the way that felt right. I’ve used the word butch to describe myself, but my friends say, “Not really, you’re softer than that.” But I’ve always presented myself as masculine. It felt good to be in that space.

Then I met my partner in college, and she helped me start treating the trauma I’d experienced, because I didn’t realize what I’d experienced was that bad since I’d lived with it for 13 years. Through therapy, I started unpacking everything that had happened to me; I started coming out too and it was such a process. Coming out was never a good thing. My mother kind of outed me. Anything that shouldn’t have been a secret, but was, was never received well. I was just told, “That’s affecting me this way, so we’re going to pray the gay out of you. Your sexual abuse wasn’t that big of a deal.” It was always about somebody else, so I’ve always been like, “OK, I’ll just process this on my own.”

I slowly started healing a little bit through therapy in college, and then my partner got a job in Vermont. I graduated shortly after and came up here, and we got a civil union. Vermont was one of the first states to allow it.

I started to experience some mental breaks; I knew there was some stuff going on, but wasn’t really quite sure what. But I kept seemingly picking myself up and dusting myself off, and then we had our first kid in 2011.

Shortly after she was born, my drinking started to pick up. I’d always done some drinking; I played rugby, and I liked beer, but it never felt like a problem to me. But the older my child got, the more I drank, and not coincidentally, it coincided with the times when the memories of my abuse started…reliving my childhood through her as I was seeing myself at those ages. Also in parenthood, you don’t exercise as much, so I lost some muscle tone and started gaining weight. I realized how uncomfortable I was in my body and didn’t really have a word for it, but it was dysphoria. I was miserable, so I drank.

We had twins two-and-half years later, and I kept drinking. I hid it really well; I was very high functioning and overcompensated for a lot of things. But ultimately I wasn’t happy. The kids weren’t enough, my relationship with my partner wasn’t what I needed and wanted it to be; nothing was right. But I kept trying to make it work without making changes and without saying anything.

PIP: What led you to get sober?

AL: Finally one day I decided to get sober, because it was either kill myself or be better for my kids. At that moment, I thought, I can’t do this, or I’ll do it for my kids. It wasn’t about me anymore. I decided to go on the South Beach Diet because it requires two weeks of no sugar or alcohol, and I was like, fuck it, I can do anything for two weeks. Maybe I’ll lose a little weight and feel better about my body. Within 48 hours, I was like, I’m a fucking alcoholic, I can’t do this. I knew I had a problem with alcohol.

I found my higher power through yoga; it helped me wonder, “If I had the courage to change something, what would it be?” I knew it would be looking at my relationship with alcohol and coming to terms with it and admitting I had a problem. I’d thought I had it under control: “I’m fine, it’s OK. Of course you’re drinking at the park while watching your kids play, and of course you packed beer in the cooler to drink on the way home from work, because everyone drinks on the way home from work while driving.” I always thought I was in control of it.

Looking back, I realize, oh my God, I’m so lucky I didn’t hurt someone; I’m so lucky I didn’t get a DUI. I was just numbing away so much stuff. After a couple days without alcohol, I was miserable and going through withdrawal. It took me about six months of stopping and starting this process. I told my partner and started telling friends. Everyone was very surprised since I’m very high functioning and a productive and perfectionist person, and I hide stuff very well. I’m better at just damaging myself and telling everyone else I’m fine.

PIP: When did you start getting into advocacy work?

AL: Part of what then led to my advocacy is getting sober and my twins going to preschool. They were both assigned male at birth, but one of them, Ryan, had been telling us since she could talk that she was a girl. When she started walking, I was like, “Wow, she’s going to make someone a lovely husband someday.” Because she was so effeminate in just the walk! I was like, “Wow, something’s there with that one!”

At 18 months old, she started demanding her big sister’s clothes. We thought, maybe she thinks she has to be a girl to like these things, or maybe she wants to be like big sister…who knows. It was a process for us. Even though we have trans friends and I understand this stuff and we have all kinds of support, it is still hard as parents to witness your kid trying to figure out who they are, or know exactly who they are and you’re not sure how to best support them.

So we lived in this gender-neutral phase for a bit; we stopped referring to her as a male. We stopped calling the twins “the baby bros” and switched to saying “you’re a big kid.” She was so persistent that we knew our kid was transgender. So before she started preschool, we talked to her pediatrician, who was so supportive and amazing.

He said, “You need to ask how she wants to start preschool. If it’s as a girl, you need to use the summer to switch pronouns and get everyone on board.” Later we asked this to Ryan: “Hey Ryan, you get to start preschool in a couple months with your brother, do you want your friends to know you as boy or girl?” And she said a girl. Almost like, “Duh, you idiots!” And her big sister, Eva, has been such a big advocate for her and has even pushed us.

One morning at breakfast before we’d even switched pronouns, Eva said, “Ryan, are you a girl? You’re a girl, right?” And Ryan burst into tears, and Eva burst into tears because she was frustrated. Our oldest had been seeing her as a girl and also kind of wanted the binary, because she knew we were in this middle phase, and the middle phase is not fun. We were like, “OK, this is a big deal, we need to make some changes.” Once we did, it was beautiful to watch Ryan’s personality shift and see her confidence grow and to see her as a happier kid: the support in the preschool was amazing. My advocacy picked up then, through education and writing.

PIP: What types of advocacy work do you do?

AL: I’m a full-time freelance writer. I started writing about being a queer parent when my oldest was born. I don’t know if you remember Cherry Girl; it was a website around for a bit, and I wrote for them. That parenting piece is what propelled my writing career. I’m on staff for a site called Scary Mommy.

I write about a lot of stuff for them, but I know my role is to educate people who want to be allies and want to be supportive, but maybe just don’t understand the stuff; I do a pretty good job of breaking things down. Someone recently called me a ‘cisgender whisperer.’ I’m good at dissecting these topics in a way that not only makes sense to people, but also adds a level of humanity and feeling. As a parent, I can write it from the perspective of having a kid, but also being in the world as me, trying to find out who I am outside of parenting.

I also have a lot of followers on my Facebook page called Family Rhetoric by Amber Leventry. Literally the day I had my last drink is the day I started that Facebook page because I needed a place to put all of my articles, and because I was getting bombarded by private messages from parents asking how to support their trans kid. Some of my articles got pretty big and people were starting to reach out, and I needed a place to talk to a lot of people at once. My public Facebook page did well, then I started doing education in my kids’ school to prepare the school for my trans daughter to start kindergarten.

As I talked to parents and became a resource, I realized there was this need for education within the community. People were wanting to have meaningful conversations with other adults and their kids about LGBTQ stuff, but didn’t know how.

There’s a conference up here called the Translating Identity Conference at The University of Vermont. I pitched a topic on how to make spaces LGBTQ-inclusive, specifically schools and playing fields; like how do we change our language? What are the things we need to be aware of to make spaces more inclusive?

Because the assumption should be there’s a queer kid in your classroom or a queer parent or an employee. Basically, change the way you speak and the way you navigate the world so you include everybody and not assume everyone is straight, cisgender, and will present themselves in a typical masculine or feminine way.

My job and what I like to do is to make people aware of their own biases and the language they use and how we can shift things. It’s as simple as walking into a classroom and saying, “Hi friends!” instead of saying, “Hi boys and girls!” It’s so simple, but what you’re going to do is create a space where if there’s a non-binary kid, or a kid who doesn’t identify as the gender they were assigned, they’ll feel included in the conversation. If you’re not separating kids based on gender, hopefully you’re not creating anxiety for a kid who doesn’t need it.

I love it, and I love to read to kids. I did an “I Am Jazz” reading on my Family Rhetoric page last week and that was really fun. People asked for more storytime. I also developed a four-part series and pitched it to the local parks and rec department and it did really well — people love it — so I’m doing more of that. I have a website, amberlevetry.com, and people can hire me to do any one of these workshops. I can gear it toward whatever you need. I’m going to do some keynote speaking this summer. I do a lot of work with teachers and mentors who work with kids.

I’m going to work with a camp up here to train counselors; they’re going to open up their all-girls camp to trans and non-binary kids, which is amazing. My hands are really in helping adults feel comfortable with this stuff so they can support kids. One of my programs is called “How To Talk To Kids About LGBTQ Topics.” Because people say they don’t know how to talk to kids about this stuff, but most of the time I’m just talking about this stuff in a way that makes people think about themselves.

It’s really about you understanding that we all have a sense of self, and a lot of our sense of self is around our gender identity and our sexuality — how do we fall in love, how do we identify, and how do we express that to the world?

If we can have a handle on that, and maybe you don’t yet, but if you can respect in yourself that you have this piece of authenticity and you want it to be supported, then you can hopefully transfer that to whoever you’re around, because they want the same thing. If you don’t understand it, that’s OK. But wouldn’t it be really nice to make space for people to be whoever they need to be whenever they need to be it?

I get people to understand the difference between gender and sex. I also explain sexualtity. I go through things like “these are the different types of sexualities, but everyone’s experience is different and not everyone wants these labels. It’s a privilege to know what people want to tell you and not a right for you to know or understand anything.”

I help people hopefully just be respectful. And I’m really approachable. I’ll tell people before I start to talk, “You can ask me anything, and I’ll be comfortable saying ‘I’m not answering that because it’s inappropriate’ or ‘This is how you can reframe it and ask it in a better way so you don’t get punched’ or ‘You should never say that again.’”

I want people to feel like they can ask questions, but then they have to then put in the work, because it’s not my job to carry the emotional labor for them. I’ll help you and get you comfortable and we can have fun with this, but at the same time, you then have to continue on with reading these books to your kids and having these conversations and not panic and not shame your kids when they ask you questions.

Because really, kids are just trying to figure out the world, and if you poo poo them, they’ll either think, ‘Oh man, this thing in me isn’t right,’ or ‘This thing in my friend isn’t right,’ and that’s where the anxiety and shame comes from, and that’s what leads to depression and self-harm and all the awful things that our LGBTQ youth are facing. And adults too — it’s because we’re taught from an early age that we’re not normal. I hope we can normalize that stuff and show that through representation.

So my advocacy picked up in part because of Ryan, and also then as I got sober and was doing all this advocating. I realized I haven’t been advocating for myself. Being sober, I realized how much I hate my body and how uncomfortable I am in my own self. I was always more comfortable being male gendered versus female. I flinched and had a physical reaction any time someone referred to me as female. Several years ago, I wondered if I was transgender, but I realized I don’t feel all male either. It was weird, I just couldn’t put myself in either box.

In my sobriety, I’m realizing how much of me I’d sacrificed to compromise, out of obligation and shame from the drinking. I realized my relationship had changed. My partner’s reaction to me coming out as non-binary and changing pronouns was difficult. I’m getting closer and closer to my authentic self, but it’s hard to know that my identity has changed my relationships.

It has created a sensation of being a burden for finally doing what I want and need and how I want to be respected — knowing that it makes other people uncomfortable. But as an advocate and educator, I often talk about how it’s a privilege to feel comfort. It’s not fair for me to feel uncomfortable all the time, so I’m asking for others to be uncomfortable so I can feel better.

I’m not asking for a lot. If you tell me what your name and pronouns are, I use them. So if you respect me and care about me, and I tell you my pronouns, use them.

PIP: What are your plans for the future?

AL: I will have top surgery eventually, when I can afford it and the time is right. I have no interest at this point in doing testosterone. I’m pretty physically fit, so I think if I can stay comfortable with that level of fitness, I’ll be OK. I lost 30 pounds in my sobriety, which did a lot for me. I do heated yoga and run, and I put energy into places that are much healthier. I do feel good about my body for the most part. I definitely range from feeling agitated to crippling depression as well, and I think a lot of it will hopefully get better with top surgery. I’m actually heading to my doctor now to talk about it!

I write for The Temper, and I’m going to slowly start talking about the way being non-binary has changed my relationships. It doesn’t feel fair sometimes to say, “These are the things I want and need to be a healthy, happy person.” At the same time, if things stayed the same, I know my sobriety is at risk; there was just so much resentment. As hard as it is to push to be your authentic self, it’s so important.

For a while I didn’t feel seen. I wasn’t being seen in my marriage the way I wanted. I recognize some of this is on me. But now I’m being seen in other places so I have that feeling to compare to. I’ve found the emotional support I need. I finally started crying; I’m finally getting to these places of healing. I’ve been processing a lot.

Thankfully I have friends and people who I can safely tell things, and they hold me and they support me and they see me cry and struggle, and it’s what I’ve needed to keep falling apart in order to put myself back together.