Janae Marie Kroczaleski, aka Kroc, was assigned male at birth when she was born in Michigan. As she grew up, she exhibited some characteristics common to little boys: she was athletic, outdoorsy, and not afraid to get dirty. But over time, she realized she felt more female, like a tomboy — not an actual boy.

But with no transgender people in the public eye at the time, she had no reference point for her feelings. After school, Kroc joined the Marines and served honorably, even being selected for presidential security duty under President Clinton, though she continued to struggle internally. When she was 23, she confessed her confusion to her future wife, who was supportive initially. That was short-lived, however, resulting in Kroc suppressing her feelings for many years. They married and had three boys, but after 10 years of marriage, they divorced and Kroc began coming out to her close friends and family.

Meanwhile, Kroc threw her energy into the sport of powerlifting. She went on to win numerous national and world titles and eventually set the all-time world record in her weight class competing as a male. But her gender issues continued to intensify, and she was eventually forced to admit to herself that she was transgender and could no longer avoid dealing with it.

Kroc planned to keep living publicly and competing professionally as male, then fully come out and transition once her sons graduated from high school. She worried about losing sponsorships and fans, but she had a steady day job as a pharmacist, so her primary concern was shielding her children from ridicule.

Then, in 2015, Janae was outed by a YouTuber who’d learned about her true identity. The video went viral, and Kroc, who by this point was a prominent powerlifter, was the subject of sensationalized news stories and lost some of her sponsors.

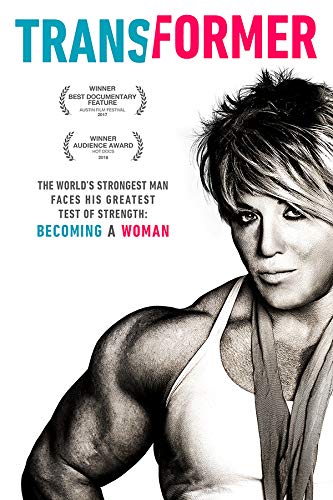

While it was devastating at the time, Kroc now appreciates that it pushed her to start living authentically. A filmmaker who had previously worked with Kroc on promotional videos saw the news about her and reached out. Eventually, she agreed to let him and a crew create the documentary film “Transformer” about her life as a transitioning powerlifter and parent.

Soon after starting her transition, Kroc believed she’d have to give up her sport and change her physique to conform to what society tells us women should look like. She lost over 70 pounds of muscle to try to appear feminine, but after losing so much strength she’d worked so hard to build, she felt even worse. It occurred to her that she didn’t have to fit into boxes or sacrifice doing what she loved.

As an out transgender athlete, Kroc sometimes presents more masculine, and other times, more feminine. She also acknowledges that due to her body, it’s hard for some people to read her as female. Over time, she has become comfortable occupying a space somewhere between the binary, and she currently identifies as genderfluid and nonbinary in addition to trans.

Kroc retired from competition after being outed, but recently, has considered returning to compete again. Due to her significant muscle mass and unique situation, she felt it would be unfair to compete as a female, and she didn’t want to make things more difficult for other transgender athletes. She feared that due to her physique and high level of success, she would be used as an argument against trans women competing in the female division. To prevent this, she decided if she does return, it would be in the male category, which fueled false rumors that she was detransitioning.

Meanwhile, Kroc didn’t think much would come of the documentary, but it went on to win awards at major film festivals. Once it went on Netflix last year, her visibility jumped to another level. Her social media accounts became inundated with messages from people inspired and encouraged by her, especially other transgender athletes.

This opened up speaking and writing opportunities. Kroc felt so passionate and excited about this work that in the fall, she quit her job as a pharmacist to do this full-time, and she’s also working on a book about her life. Kroc, now 47, still resides in Michigan to be near her family. She knows it can be hard to cobble together a living as an activist, but she’s thrilled to help make a difference in the lives of LGBTQIA people. This is her story.

Profiles in Pride: Hi Janae, you mentioned you use she/her pronouns, but how do you currently identify?

Janae Kroc: A combination of gender fluid, trans, and nonbinary. It’s difficult to explain. We want to label things so we understand them, but labels can be limiting. I’ve always had masculine aspects to my personality — but not my gender identity.

Though there is also a degree of fluidity with my gender. There are some days and situations when I’m very feminine, and other times I’m more masculine. There’s an ebb and flow. Some days I feel more one way than another, but there’s never a change in my identity. Even the days I feel the most masculine, I still have a female gender identity, so that’s why I use all three. I think that’s the most accurate way to describe myself. I’ve had a few trans girls be like, “You can’t be nonbinary and trans, it doesn’t work that that way.” I try to have the conversation and explain why I identify the way I do. It’s not that simple for me.

PIP: That makes sense! When did you first realize you were transgender?

JK: Around 5 or 6 years old, I found myself daydreaming about being female. I wasn’t picturing myself doing stereotypical things that people might think. I wasn’t like, “I wish I could play with dolls.” I just saw myself as this little athletic tomboy, climbing trees, playing baseball, riding bikes, and catching frogs and snakes. A rough and tumble girl with a ponytail and a baseball hat. It was really confusing for me; I didn’t know why most of my interests were traditionally masculine, but I felt like I was supposed to be female.

As I got older, I did have a very strong interest in makeup and fashion. Even going to department stores for me growing up was torturous. I wanted so much to be able to go to the makeup counter and look at everything and try on shoes and purses. I was always drawn to it, but it just felt like this dark temptation. I’d already been conditioned by society that how I felt was wrong and something was wrong with me, so I felt guilt and shame. Walking by those sections, it was like a strong magnet pulling me in, but I knew I couldn’t do that and couldn’t tell anyone.

PIP: At what stage in your life did you decide to come out?

JK: In my teenage years, and when I was in the Marine Corps, I didn’t really acknowledge or allow myself to accept that I was trans even though all the signs were there. Looking back, it was very clear, but I’d do things to convince myself otherwise. I’d remind myself, “I like sports” and “I like women.” All the trans women I’d heard about were very feminine and attracted to men, so I thought, “I can’t be trans, I’m not like that.”

I was 23 when I first told someone. It was my ex-wife, when we were friends, before we started dating. I had almost told one of my best friends in the Marines, who was very open-minded. He’d grown up in New York City and was exposed to lots of different things, as opposed to me who grew up in a small town in rural Michigan.

He sensed something different about me, and I was very open about being a virgin, which for a young Marine wasn’t common. I was athletic, outgoing, and I was social, so it didn’t make sense to people. Back then, all people knew was just straight and gay. I found out later there were rumors I was gay because I never had serious girlfriends.

My friend asked me lots of times, and we’d have deep discussions. I’d talk around it and he knew something was there, but I was too terrified about what might happen if people found out. Back then I would have been dishonorably discharged if anyone in my command found out I was trans. I wanted to tell him, but at that time, I didn’t know how to put it into words. I was so close to opening up to him, but I was just so scared.

So the first person I told was my boys’ mother when I was 23. She actually guessed, and I couldn’t bring myself to deny it. Still, I couldn’t really explain it. She was supportive initially, but that didn’t last long. Then she got really uncomfortable with it, so I went back to suppressing it for about another 10 years.

I remember in my first semester at college, I went to the library and checked out every book they had on transgender stuff. The Internet was just starting and there wasn’t much good information, and the books were written by people outside the community and were clinical and inaccurate. I was researching and trying to come to terms with it. I basically started coming out towards the end of my marriage when we started getting divorced. First to my closest friends and then my family. I was in my early thirties. It was a long, slow process at first.

PIP: Did you have concerns about how transitioning would affect your powerlifting career?

JK: I did a couple of competitions in high school and some in the Marines, but I got really serious about it in my early twenties and was competing year-round for the next 15 years. When I started coming out, I was just getting to the national and world level. I’d already placed top three at nationals a couple of times and qualified for the Arnold Classic. I hadn’t won anything huge yet, but I did shortly after that.

Once I won the Arnold Classic, my first world championship, that’s when I first started coming out to all my friends, training partners, some of my sponsors, and some of the lifters I competed with. It was still a tight circle of people I felt close to. At first when you start coming out, it’s so difficult and you’re so nervous and scared. Then later on it’s just like, “Oh, by the way, I’m trans.”

I told one of my main sponsors, Elite FTS. They’re very well-known in powerlifting, and the owner, Dave Tate, is a great guy. I started with the company in 2006. I got close to Jim Wendler, another popular figure who was there at the time. He came across as a stereotypical power-lifter: muscular, tattoos, shaved head. But I also recognized that he was very open-minded and a creative writer; not your typical meathead. I came out to him since I had a sense he’d understand. He did and was really supportive.

I asked if he thought Dave would be OK with it. He said, “I think so, but it’s so hard to say.” At the time, I was one of their most popular athletes, so I wondered what kind of impact that would have on the company. I made the decision to tell Dave, and he didn’t expect it, but he was super cool about it — he had an uncle who had transitioned! Her life was horrible before, and she was so much happier after.

We had a lot of good conversations about how to handle it and who to come out to. Yeah, I worried about losing some sponsors and my fan base, but my main concern was how it would affect my boys. While I told them when they were young, I thought they might have a hard time with teachers, coaches, and getting teased at school. Ultimately, I told more people, but I decided it was probably best to wait until my sons graduated high school, and then I could come out about everything and really get involved in activism.

Then I got outed almost five years ago, and that option got taken away from me. In hindsight, it was a good thing. There were some bumps in the road; I lost some of my biggest sponsors, and I lost a lot of fans. But all in all, it ended up being a good thing.

PIP: If you’re open to speaking about it, how were you outed as a transgender athlete?

JK: It was a YouTube vlogger who did a gossip page about strength sports. Somehow he caught wind of it. I was getting more and more open about it. I’m a really honest person and I don’t like to lie.

I was very open with the people I competed against; a lot of them became really close friends of mine. Once I told a few people, others would hear about it and ask me, and I’d always acknowledge it was true. I didn’t ever show up at our events or dinners presenting female, but they all knew about it.

Some of the guys would bug me: “Hey, when’s Janae coming to dinner?” But I didn’t want to turn into a freak show. While a lot of the people were supportive, I knew some people would take pictures and it would get reposted. I just tried to keep it separate. Looking back, I don’t know how I had hidden things for so long; I guess it was primarily out of fear.

Somehow this guy knew someone who knew, and he found out. He made a video about it, and it went viral within hours. It turned my world upside down. I’ll never forget it; I’m at work at 11 a.m. on a Monday morning and my phone starts blowing up. First, it’s my friends telling me I got outed. Then in half an hour it’s TMZ and Inside Edition texting my phone wanting interviews! I’m like, “What in the world?!” It was crazy.

Maybe I was a little bit naive about how big of a deal it would be. I expected a lot of the reaction I got in the lifting world, though It was more supportive that I’d expected, split 50/50. A lot of people were very supportive — more of the fan base than I was expecting. But then there were a lot of terrible things being said. I had people messaging me that they’d burned the posters I’d signed for them.

All in all, it was a little better than I expected. I had a number of prominent people in the sport reach out and be supportive, so I was pleasantly surprised by that. It was cool to see some of the biggest names in the sport say, “Hey, I really respect what you’re doing.” All my friends stuck by me, so all in all it ended up going much better than I feared it might.

PIP: Wow, I can’t even imagine. How did the documentary about you, “Transformer,” come about?

JK: One of the companies that dropped me, my biggest sponsor, was MuscleTech. I was one of their main athletes, and they filmed all these videos of me training. Six months before I got outed, we were shooting a video, and the videographer did some freelancing on the side. He’d shot me doing a bunch of stuff for MuscleTech ads, like heavy squatting and doing hardcore lifting stuff.

When I got outed, he heard the news and remembered me. His name was Brian and he ended up being the cinematographer for the documentary. He heard the story and remembered me and contacted Michael, who became the director, to say, “Hey, I just filmed this person a few months back and I think this story is really interesting.”

He told Michael about me, who reached out and said, “I’d like to come to Michigan and sit down with you and explain what I have in mind. No cameras, no pressure. Just want to tell you what I’m thinking.” I didn’t want to be sensationalized. I was concerned it could be turned into a freak show. I had already dealt with that a bit after I got outed and did tons of interviews.

I really didn’t expect the mainstream attention; I was on TMZ, Inside Edition, and nationally syndicated radio shows. I knew it would be a big thing in the lifting world because it was such a crazy story. Some of these people exploited me a little bit, especially Inside Edition, even though I discussed with them beforehand that I’d only do an interview if it wasn’t sensationalized. They said sure, shot all this footage, and didn’t use any of it and turned it into a total dress-up show.

So I learned my lesson with that. I addressed my concerns with Michael. My goals for anything like this are to help inspire people like me and try to educate people who don’t understand. If we can do those things, I’m all for it. But if I’m turned into a freak show, I don’t want any part of it; I don’t care what you’re offering. He said, “No, I just want to tell your story, I think it’s something people need to hear.” Meeting with him in person, I really felt like he was sincere. I said, “OK, let’s do this!” I was right; Michael and the whole crew turned out to be great guys.

PIP: How did being in that film change your life?

JK: It was crazy and surreal for a little bit. We did the festival circuit before it was released. That was in the fall of 2017 and spring 2018. The first film festival was in Austin, Texas, which is a very LGBT-friendly town, but I didn’t think it was going to get any attention or expect anything to happen. When we won the audience award and critics award, I was completely shocked!

The big one was the Hot Docs Canadian International Film Festival in Toronto — it’s the major festival for documentaries. There were some really big mainstream documentaries we beat. Typically they’d show the film, have me sit in the audience or wait outside, and I’d come do a Q&A as soon as the film was over. People had a lot of great questions. We’re in these big theaters, and one of them sat 700 people. At the end, we got a standing ovation, which was really cool to see!

I don’t know that it really had much of a direct impact on the rest of my life, at least initially. At first it aired on the CBC Network in Canada and was available on Amazon Prime and iTunes, but when it hit Netflix, that was much different. It had such a bigger audience. Even though it only went on Netflix in the US, that’s when my social media blew up a lot more. I had a fair number of followers from my lifting career and the people who knew me already, but once it hit Netflix, it was crazy.

In the month or two after that, I’d log onto Instagram and new people were constantly following me, and they’d all say, “Oh my gosh, I saw your story on Netflix.” It was really shocking to see how many people Netflix reaches and what a big platform that is.

PIP: I know you left your job as a pharmacist and you’re working on a book. Do you think the documentary gave you the platform to step into activism?

JK: That’s what I’m really hoping, and that’s what I’m trying to do. I had lost my job in pharmacy, and it took me a year to get another job. I actually submitted 51 applications before I got my first interview; that was really surprising and tough. But once I got that first interview I was hired and went back to working at a hospital as a pharmacist, and I did that for a year and a half.

In between pharmacy jobs I tried focusing on activism and writing full-time, but I wasn’t making anywhere near enough money. To scrape by in-between the two jobs, I went back to training and was writing training and diet plans for other people. I did a little writing but was just too busy focusing all my time on making enough money to cover the bills.

I eventually got the other pharmacy job, but I knew I wanted to focus on the activism stuff full-time. After speaking at Ellevate’s Mobilize Women Summit in New York and the GRRRL Live Conference in Las Vegas last summer, it just felt like this is where I need to be.

I’m there and connecting with people and it’s such a good feeling. In New York City, talking with a bunch of people after I spoke, it clicked: This is what I need to be doing. This is how I can really affect other peoples’ lives. This is what matters.

I put my notice in at work a couple weeks later. They asked me to stay on a few months to find a replacement, which I agreed to, then in October I left the pharmacy! So now I’m doing a lot of writing, speaking, and educating. The reach that Netflix has definitely gave me the opportunity to have a bigger audience and exposed me to people who had no idea who I was or what my story was.

We have some potential things in the works that will expose me to a bigger audience. I have a manager and I recently hired a media person, and we’re really focusing on launching my YouTube channel. He’s actually trans himself, so he’s not only a super talented media guy, but he also understands my vision and what we’re trying to do. So it was a win-win for both of us. We recently shot a couple dozen videos and he’s editing everything. My plan is to post bi-weekly.

People have this assumption that because I was in a documentary that won awards, I’m rich now. Documentaries are not big money-makers. Even in powerlifting, when I was in magazines — you don’t get paid to be in a magazine! Sometimes I do appearances for free because I believe education is important. It’s very difficult to make a living doing this unless you have a major Hollywood or book deal. But I believe in what I’m doing and I think it’s really important. It’s what I love doing and I’m passionate, and if I can make a living at this, that’s my dream.

PIP: Have you received a lot of positive feedback from people who watched the documentary?

JK: That’s been huge; that’s been the best part of all of this. I literally get messages every day. I feel bad that I can’t respond to everyone. I try really hard to, but once it hit Netflix and my following went up so much, the volume of messages makes it impossible to reply to everyone.

I still get messages daily from people saying thank you for being open and honest. Usually it’s “You’re helping me come to terms with who I am” or “I’m so afraid to come out.” Or people like me who came from an athletic background and are into lifting but also have gender identity issues, saying, “Gosh, I didn’t know anyone was like me.”

They’re all important, and I really appreciate people taking the time to share their stories with me. I also get a lot of parents who thank me because of their children, either seeing the documentary or saying, “What you post is helping me come to terms with my own child and helps me be supportive to them and understand them.” I’ve had dads message me and say if it wasn’t for me, they’d basically still be rejecting their child. You hear things like that, and how can you not go forward with that?

PIP: Wow! I truly believe that type of visibility can be lifesaving.

JK: Yes; when I grew up there was no social media or Internet. I honestly didn’t know there was anyone else in the world like me. I didn’t even know what the words were or how to describe it. Even after hearing about trans people, there was really nobody I could relate to.

Donna Rose wrote a book called Wrapped in Blue. In early Internet days I was buying every book trans people had written, and hers was one of the early books I read. She was a college wrestler. I’d wrestled from a young age, all through the Marines and after, and it was my favorite competitive sport in high school. I remember at one point in the book she was talking about working out hard and getting big and muscular and being this high-level athlete.

It clicked in my head: here’s this person who’s this athlete, who everyone perceives as being very masculine and alpha. This lightbulb went off and I said, “Holy shit, I’m trans.” It was good and bad at the same time. It felt really scary, because up to that point I’d been able to lie to myself and deny it.

I’d read some early stuff online that someone had written, I’m sure with good intentions, but it was how to tell if you’re trans or not. I didn’t fit all of their criteria, so I said, “I’m not trans, that was a close one!” But then reading Donna’s book, it definitely sank in. At that point I had to acknowledge I’m trans, no doubt about it. It was this ‘oh boy’ moment of what do I do now?

As someone who doesn’t fit the mold of a lot of trans women, I was shocked to see how many people can relate to that and don’t necessarily fit in those boxes. I really believe there’s a spectrum. It’s not either/or; there are a lot of us who fit in-between somewhere.

I think there’s a lot of people who don’t identity as trans or nonbinary but can relate, and I think there’s a lot of people who can relate to not feeling like you’re like everyone else or not fitting in.

I think that’s a big part of my story as well. So many of us went through life pretending or hiding the parts of us we were afraid everyone is going to reject. The ironic part is that so many of us are doing the same thing. If we were all just honest and open about who we are and the things we enjoy, I think everyone would be shocked — I’ve been hiding all the same stuff everyone else has! I just remember what it’s like to be that scared little kid who’s all alone and thinks something’s wrong with you, and you’re this freak who’s broken. It’s a horrible way to grow up. I don’t want other people to have to go through it.

PIP: Absolutely. I remember reading that you have considered returning to competing in male powerlifting after beginning your transition; could you talk about that?

JK: Yes, it unfortunately started rumors that I was detransitioning. The big struggle for me was my passion for strength training and competing. At my core, I’m an athlete and I love to compete. I loved my powerlifting career, and strength is something I’d been passionate about my entire life. Like a lot of people, I’d been conditioned to believe it was associated with masculinity, not femininity.

When I started transitioning, I felt like I had to reject these things. I had to be this thin, feminine, Victoria’s Secret-body-person to be my authentic self, which I now believe nothing could be further from the truth. It’s still very difficult being this big muscular person who also identifies as female. Even cis-females who are passionate about the same things get a hard time from society. Family and friends saying, “Don’t get too big or too strong” or “You’re starting to look like a man!”

Being trans, when I’d hear those things, it was especially difficult and stirred up all these feelings. Initially I lost 72 pounds, but then I realized it was making me unhappy. Here’s all this hard work I’ve put in for years for my favorite thing in the world, and I rejected it and gave it up.

I kept starting and stopping transition, as far as what you’d consider a traditional one on hormones and surgeries. I felt like it was all or nothing; I have to do everything society tells us to or I can’t transition at all, so I kept going back and forth. It was super confusing. After I was outed, I started getting close to a lot of female lifters. These were girls I knew and some I was even friends with, but I’d never had these deep girl-to-girl type conversations. I thought, “Oh my god, here are people who completely understand what I’m dealing with.” They didn’t have gender identity issues, but they shared the passion for wanting to be more muscular and stronger and the pressure from society not to do so.

That helped me figure so many things out and say, “I have a female gender identity and I have a passion for strength training, and that’s OK.” I felt if I had to transition, I would have to leave competition. But I realized no, I can still lift and be me. Some people don’t understand that. It’s hard to function in society as someone who stands out a lot. Even when I’m presenting very feminine, especially walking around at 250 pounds of muscle, they’ve never seen anyone like that. It draws attention, and I understand it. I don’t hold that against people. I’m sure if I was in their shoes I’d look too; it’s not something you see every day.

I haven’t competed since 2013, so it’s been seven years, and I really missed competing. Okay, so if I go back to competition, where do I compete and in what sport? A lot of people were confused when I announced I’d be competing in the men’s division. Some assumed I thought trans people shouldn’t be allowed to compete in the class they identify with. I don’t. Some believe I’ve detransitioned or wasn’t trans anymore. I don’t care how you dress or what you do; if you’re trans, you’re trans. It doesn’t matter if I’m butched up and looking as masculine as I can look or looking super femme — I’m the same person inside.

I chose to compete as a male because there were two things I was afraid of. There’s a big thing with trans athletes right now, especially trans women. I didn’t want to do anything to harm the community and the sport I love. I didn’t want to be the person everyone pointed to and said, “This is why trans women shouldn’t be able compete in cis women’s competitions.” I was very afraid it would happen. I had no doubt it would happen, and I didn’t want to take that risk.

I’m mainly a powerlifter who’s done some bodybuilding. I’ve competed in both sports; I even did one Strongman competition in the late ‘90s and enjoyed that as well. At my core I’m a powerlifter and that’s where I had the most success. But I’d achieved all my biggest goals. My biggest goal was to get the record in my weight class, which I was able to do. After that point, there was this letdown. I chased my goal, now what do I do?

Because I was built fairly well for a powerlifter, I thought maybe I’d try to be the first powerlifter who’s an all-time world-record holder, to also become a pro bodybuilder. No males had done that. I wanted to be the first person to do it. I switched over to bodybuilding and competed there for four to five years. I was working toward that goal, and I’d already won state championships and competed at nationals. But that’s when I was outed. Then I decided to transition, lost all this weight and then that derailed all those plans.

But I kept getting these itches and urge to compete again and it felt like unfinished business. I thought about it for a long time and wondered how to explain this to people. I don’t want people to misconstrue what’s actually going on. For me, it’s being able to compete again and challenging myself and competing in the toughest way possible. It’s also a good opportunity, since it’ll be talked about a lot.

When I announced a few months back about coming back, it got more attention than I expected. People are saying I detransitioned, but it’s not the case. For more than a decade, my presentation has varied from day to day. Part of it is how I feel, and part of it is that, unfortunately, is the hand I’ve been dealt.

I’ve tried hard to appear much more feminine. I’ve undergone facial feminization surgery. I had vocal feminization surgery and it certainly helped, but my voice isn’t as feminine as I’d like, so I often still get read as masculine on the phone. And at my age, my body didn’t respond to hormone therapy the way I was hoping and I didn’t get much breast development or other changes I’d hoped for. And I’ve also lost too much hair to grow my hair out, so I often wear wigs. So despite my best efforts to appear exclusively female it’s still not possible for me to pass most of the time.

I really wish my body was more feminine; I wish I had more breast development, I wish I was curvier, I wish my voice was a little higher. And I would love to be able to grow my own hair out. That’s part of why people would see me and think I’m presenting very masculine. I’d say my presentation is now what people would describe as very queer. My nails are always painted, I carry a purse, and 90% of the clothing I wear is women’s clothing. But I don’t wear a wig or makeup every day. With the wig, it’s more just a practical thing. They’re hot, they’re itchy. With me being super active and loving the outdoors and the beach, it just doesn’t work.

So my presentation is something that looks fairly masculine a lot of the time, and other days extremely feminine. I hate to even use those words, because what is masculine and what is feminine? I think those terms are overused. There are women who embody these things, and there are men that embody these things, and all along the spectrum.

So if I do return to compete in the male division, I’ll be doing so because I don’t want to harm trans athletes; I want to go back for a goal I never finished and am trying to reach a bigger community about who I am. I think it’ll open up more conversations. I‘m trying to make sure people understand I’m still trans, I’m still the same person, and nothing has changed. I don’t want people to misconstrue this as, “I don’t think a trans woman should be able to compete.” There needs to be more research, but all the research we have indicates that letting trans women compete is the right thing to do. I don’t want people to misconstrue what I’m doing as a rejection of that.

Keep up with Janae on Instagram @janaemariekroc and on her website, JanaeKroc.com.

Her true testament is that her 3 sons are supportive and loving. I’ll say this I wish I could be strong like her. Male or female💪!

[…] tells the story of Janae Kroc, a former Marine and competitive bodybuilder and her transitioning process. She suffered a lot, but […]

Hi. Janae. You are awesome. I think you are gorgeous, Honest and have a sense of real. Wish I could meet you. Love and respect. Norma. Jean