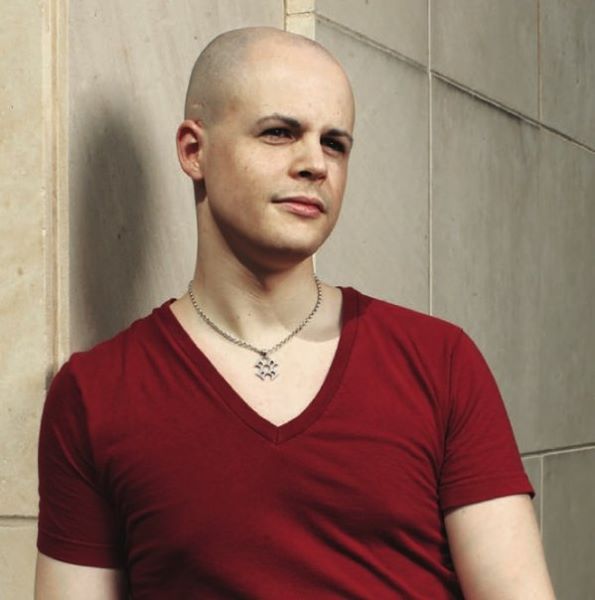

Kathryn Gonzales was assigned male at birth, but she never felt quite like the other boys. She came out as gay when she was 13 since that label felt the most right at the time; she was a child of the ‘80s, and there was little public knowledge about trans people. But when she was 19, she watched a movie featuring a trans woman and suddenly realized that’s who she was.

Around the same time, she dated and then married someone who was just coming into his identity as a gay man in his early thirties. They lived in Austin, Texas, and together and separately navigated the process of coming out and living authentically.

Gonzales started to transition multiple times, but because her journey didn’t line up with the typical “trans narrative” she observed, she kept putting things on pause. But at 25, her life changed overnight. She was sexually assaulted, and the incident left her HIV+. Faced with the fear of dying without people knowing who she really was, she realized it didn’t matter that she didn’t fit the typical trans narrative, and she proceeded to transition.

Meanwhile, she struggled to find the right career path, and after obtaining her MBA, she attempted to grow her consulting business in size and scope, but nothing seemed to pan out quite right. In her free time, she also volunteered for nonprofits. One was Out Youth, an organization that supports LGBTQIA+ youth in Central Texas through a variety of programs and resources, including an in-person drop-in center in Austin.

In 2005 Gonzales started helping the organization, first with volunteering. This turned into paid consulting work and eventually a full-time job, and she currently serves as the organization’s operations and program director. She didn’t plan for this to be her career, but she’s found that it’s her true calling and passion. Giving LGBTQIA+ youth a safe place to be accepted and feel a sense of family and unconditional love — especially if they don’t get that at home — is her life’s work.

Recently, she was also tapped to co-author the book Trans+: Love, Sex, Romance, and Being You, which was published by an imprint of the American Psychological Association. While she’d never written a book before, her co-author, Dr. Karen Rayne, wanted to enlist the help of an expert on trans youth. Gonzales fit the bill, and she savored the opportunity to help trans youth and those who love them navigate growing up. She says one of the most important takeaways from the book is that the only constant is change, and that’s OK. Her own life proves it.

This is Gonzales’ story of navigating her identity, overcoming the typical trans narrative, and accidentally finding her calling of helping LGBTQIA+ youth feel loved and understood.

Profiles in Pride: What was your journey to coming out as transgender?

Kathryn Gonzales: I think this is very common among trans people; I kind of always knew that something was different, but I didn’t know what that was. There’s a whole chapter in the book about the trans narrative, so I’ll be the last person to say, “I always knew I wanted to be a woman.” That is not true; I just knew I was different from everyone else.

I have a recollection of being 7 years old and my mother turning to me in the car and saying, “You know, if you ever wanted to be a girl, that’s OK.” I was like, “Hmm, that’s weird, I wonder why she said that?” and I went about my business.

I came out as a little gay boy at 13, because that was the only language we had. And I was very masculine presenting; it was drilled into me for my own safety I needed to kind of blend in. Not much blending in is happening nowadays!

When I was 19 I came home from college and was working a part-time job. I came home one night and Bravo was showing “Priscilla Queen of the Desert,” and I still distinctly remember the moment. There’s a scene where they pull up to a lake. They splash around and have fun, and Bernadette, the trans woman, lays back and floats for a while, and just takes a moment. Bob comes up offers his hand to help pull her out of the water. He says, “Can I help you, ma’am?” or something like that. At that moment, I was like, “Oh, got it, that’s what I am. I’m Bernadette.”

PIP: Once you had that realization, what happened from there?

KG: From there, I met Rodney, and we got married. He was just coming out at 32 as a gay man, and there I was trying to come to an understanding of who I was. That developed over the years; lots of therapy, lots of conversations, lots of research.

I mentioned it in the book too; I don’t believe I detransitioned, but I definitely stopped transition a couple of times. And by a couple, I mean four. The running joke in the family is with me it’s never third time’s the charm — I like to go a little extra and say the fifth time’s the charm! That’s the one that stuck. I think the important context is the reason it stuck that fifth time was I had been sexually assaulted and diagnosed with HIV as a result when I was 25.

Wow, I can’t believe it’s been almost a decade. I’d assume unlike most people who are 25, I really had to face my mortality in a way that most don’t. The thing that kept coming up was this fear of dying. Actually, I wasn’t afraid of dying; my fear was dying and people not knowing who I was. If I was going to die, it was at least important to me that people knew who I really was. That really spurred along the transition. I started hormones at 27.

PIP: What do you feel held you back the first few times you attempted to transition?

KG: The trans narrative. I’m just gonna get up on my soapbox. Christine Jorgensen transitioned in the 1950s in a very public way, very similar to Caitlin Jenner. The most iconic image of Christine Jorgensen is after she’d flown back from being away for years.

She’d gone away as this masculine idealized version of a sportsman. She came back and the plane door opened, and she emerged and the flashbulbs went off because no one could believe that she’d so thoroughly traversed the binary. For a while, the press and the public were enamored with the thought of this, and as usually happens, people started becoming less and less enamored.

It rears its head again in a big way. There was a lot of stuff going on in the ‘70s, but really where I see it taking root in a way that affects my generation and the generation I work with now, was late ‘80s and early TV ‘90s talk shows. During sweeps week, they’d bring on “trans women” and parade them around as spectacle. What we’ve found out all these years later is most of the time, they just found cis male actors and dressed them in women’s clothing. And there were almost never any trans men.

So the public had this spectacle, this version of being a trans woman, that looked scary. It scared me. Going back and looking at it, no wonder everyone reacts the way they do. And it enforced this trans narrative, this checklist, this timeline, that informs trans women how we’re supposed to transition.

Which is, you come to understand who you are, and a clock starts counting down from two or three years. You go and get the therapy and you do your real-life test and you get on the hormones and you do all the surgeries and you move to a different town and nobody knows you who you were before and you get a new job in a different field where nobody knows who you are. And you don’t talk to your family ever again and you burn your baby pictures, and your entire life becomes about making other people as comfortable as possible with your existence, instead of the process being about becoming comfortable with our own existence.

It’s something we try to hold dear in my work at Out Youth and something that my co-author Karen and I really wanted to capture in the book, which is that the only fundamental constant in our universe is change. Even the speed of light changes as it approaches the event horizon of a black hole. Nothing is fixed except for the fact that everything is changing.

We wanted the kids reading the book, just like we want the kids here at Out Youth to know, that no matter how many times things change, we will always be here, and that’s what family does for one another.

PIP: I’d love to hear more about your work as Operations and Programs Director at Out Youth!

KG: Working at Out Youth is and has been the greatest honor of my life. We’ve been around for 30 years; we were founded in 1990 by two graduate students who were studying social work at the University of Texas at Austin. They’d both grown up as queer-identified folx in Texas in the ‘70s and ‘80s and wanted to make things better.

They did their research and ultimately came to the decision that they were going to start peer-facilitated support groups. They created spaces for youth to talk about what they were going through. So, in living rooms across Austin, we began.

It’s important to remember, in 1990 most people didn’t have the Internet, and if they did, it made a terrible noise and was very slow. There wasn’t Facebook and Instagram and all of these means to spread the word. I came to find out a couple of years ago that we used to make photocopies of our flyers and send our volunteers to public libraries across Austin. They’d slip the flyers in between the pages of LGBT-themed books and into the pages of dictionaries where youth could find the definitions for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans definitions.

Thirty years later, we’ve come a long way. We’ve vastly outgrown our space, but what we’ve always done and will never change, no matter what comes next, is we give our youth and their families a place where they’re loved, acknowledged, and accepted, exactly as they are. No matter how many times that might change. That‘s not us saying that we think sexual orientation and gender identity is a choice, it’s simply an understanding we are always growing we want to be there as a support along the way.

PIP: Does Out Youth ever support kids whose families are not accepting?

KG: Yes, all the time.

PIP: How does that work?

KG: The nice thing about Out Youth is that youth don’t need any permission from anybody to access the community drop-in center. We don’t ask how they got here or if anyone knows where they are, because we know in some cases if parents knew where they were, they wouldn’t be welcome home that night.

Out Youth has always been a place for anyone, regardless of identity. If anyone feels like the other or on the outside of things, they can come and feel part of a family. In fact, I end all of our new client orientations the same way, so Ie can tell the kids without loving families:

“This is your first time here. You could come back a thousand times or never again; that wouldn’t change the fact that you’re part of this family now. We’ve been here for 30 years and have over 25,000 family members all over the world. Whether or not you expected to join a big family when you woke up this morning, you did. So that is to say, if you need anything now or in the future, and that could be 10 or 15 years from now, you call, text, email, whatever it takes to get a hold of us, and we will do our best to help. Because that’s what family does for one another. Got it?”

You know which ones have not experienced a sense of family before, because they’re the ones who start crying. For the first time they feel part of a family that loves them.

I was awarded Out Youth’s highest honor at our Glitz Gala last year, The Bill Dickson Award, which was really weird to receive at 33 — a legacy award at 33! Through a combination of events, I came to understand that it was an accidental legacy. I wasn’t supposed to be at Out Youth; it wasn’t the plan. But I ended up here anyway.

The question came up in a lecture I gave at St. Edward’s University a couple of days before the gala. They asked me what my legacy was. I said, “It’s interesting you asked that, because I’m about to get a legacy award, and to me, it all seems like an accident.”

You know, what I carry isn’t the number of youth we served, the outcomes, or the metrics. Even for me, someone who’s so obsessed with story, it’s not about the stories either. I know we’ve done our work. I get fed by our work when I check in with a new youth at the end of their first night and ask “How was it?” And nine times out of 10, they’ll say, “I like it here. I feel like I can breathe.”

If we are able to give our youth four or eight hours a week to just be themselves and breathe and not have to protect and wall off their hearts for fear of being attacked or maligned or kicked out, then that’s plenty legacy enough for me.

PIP: It’s lifesaving work.

KG: And life-changing. That’s the nice thing about this work; the older we get, the further along we get, it becomes less about life-saving and more about life-changing.

PIP: What do you mean by life-changing work?

KG: The prevalence of suicide and homelessness has changed. I don’t ever want to imply it’s gone away or lessened to a significant extent. But our mission and work has shifted from saving lives to making sure their lives have been changed enough, that we build stronger youth. So they can go out and change the things we haven’t been able to change yet.

If we can intervene to save a life, we certainly will, but we came to understand that it was no longer enough to keep them alive. Yes, we had to keep them alive, but we also had to teach them how to thrive when they could no longer be here at Out Youth. In that way, we operate as a family and in a parental role.

PIP: I love that. You mentioned it was accidental that you ended up at Out Youth. What was your original vision for your career?

KG: Well, that depends on which ‘me.’ At 5 years old, I desperately wanted to be an elementary school janitor, I was obsessed with vacuum cleaners and the janitor at the elementary school where my mother taught was so kind and got to play with vacuums all day!

Going into college, I went into film school. I assumed I’d be a filmmaker — the next Spielberg. I got an MBA and started a consulting firm along the way. I ended up at Out Youth entirely by accident. I was graduating from the University of Texas and applied to a job there. In my youth and naïveté, I thought the job was already mine. It was not. It was very clear five minutes into the very first phone interview.

So I had no plan and was kind of adrift for a minute. I became the founding executive director of a youth political organization, which I left when Rodney’s dad passed away, so I could take care of the family. I started as a volunteer at Austin Gay & Lesbian International Film Festival and eventually worked myself into a job there. While there, I started a queer youth media project and ended up at Out Youth for two weeks each summer teaching filmmaking.

I still had my consulting firm at the time and Out Youth needed a development consultant, so I was the one tapped for the role. I think it’s very interesting to point out that I’ve never gotten a job I have applied for. I’ve worked myself into every job I’ve had.

My history with Out Youth started in 2005. As a hard-of-hearing person who was encouraged to learn sign language because the doctors weren’t sure how far my hearing loss would go, I was tapped by Out Youth to interpret for a youth advocacy event at the Capitol and stuck around. I volunteered for a while, led summer camps, became a part-time employee, and then full time. It wasn’t the plan, but it was exactly where I needed to be.

PIP: I’d love to hear about your book; how did you end up being a co-author, and why did you want to be a part of this book?

KG: My co-author Dr. Karen Rayne, wrote Girl: Love, Sex, Romance, and Being You with Magination Press, an imprint of the American Psychological Association. The way I understand it is that when she negotiated writing Girl, she had two things she was very set on.

One, that the book would speak to any young person who identified as a girl. It wasn’t a growing-up guide for cisgender girls, but rather for girls because trans girls are girls. Second, that Magination Press agree to publish a growing up guide for trans youth.

Karen finished Girl, and they approached her and said, “OK, we’re ready for you to write the trans book.” She was like, “Well, I’m a white, lesbian, cis-person, I’m not the one who should be writing this.” She reached out to several trans people who were published authors, and nobody wanted to pick it up.

So she reached out to me and said, “Have you been published before?” I explained that I’d published some articles, but nothing long-form. She said, “How would you feel about writing a book for trans youth?” I wasn’t sure, but she asked about co-authoring. It was the smartest way we could have done it; I brought the lived experience of being trans and my work experience with trans youth, and she brought her vast experience in biology, anatomy and sexual health, and teaching comprehensive sex ed to teenagers.

It was the perfect approach. Her tone and my tone were very similar; very matter-of-fact but a maternal voice throughout. A constant reminder to the youth reading it that what they read may cause dysphoria, and it may be uncomfortable. They don’t have to sit in it. They can scribble out every time penis is used and use a different word if they want to. It was about getting the information into their hands.

My favorite part of the book is the introduction, where we remind them that in the past, in our history, in cultures all over the world, our people were revered. We held very special places. We weren’t discriminated against; we were honored. So we remind them that their ancestors were considered no less than gods and invite them to carry that forward as they read the book and carry that forward in their life. That nothing is static, everything changes. We wanted them to remember where we came from.

PIP: What are your hopes for the book and how it might help people?

KG: As a little gay boy who got a puberty book that was just terrible, I hope there are trans kids out there who will find the book in a library, or someone who loves them will get the book into their hands so they can feel less alone. We know the leading contributor to trans youth suicide rates is family acceptance or rejection and an extension of that is loneliness.

That’s why we felt it was so important to include youth voices in the book. We have six youth authors who contribute journal entries relating to content throughout the book. If a reader feels alone, they can turn the page and there’s Luca talking about their lived experience, so they know they’re not the only one going through these things.

I’m also excited that we used QR codes since it’s hard to click a link in a paper book! Readers can scan QR codes to access resources. It takes them to our website, thetransbook.com, where they can pull that resource and find others. They can also connect with us, the authors. It was our hope that everything would extend beyond the book, into a digital space, where we know that kids are already living.

PIP: Did you have a certain age group in mind when writing the book?

KG: I sometimes say teens, but actually the audience is more 10-20 years old. Pre-puberty to post-puberty/early adulthood. I’ve been very insistent that the book is for trans youth and anyone who loves them because there’s not a single thing in that book I wouldn’t have wanted my parents to know too.

PIP: Before we go, is there anything else you want to share?

KG: The one thing I always want to point out is that I don’t imagine this as the be-all and end-all of trans knowledge. We made that very clear at the beginning of the book, too. It’s meant to be a snapshot in time, and we hope the information will be relevant for the near future. We also acknowledge there will come a time when the language just doesn’t work anymore because we’ve moved along. At that point, I imagine we’d do a revision and we’d certainly be open to that.

I’ll reiterate, we aren’t the experts. The experts at the end of the day are the kids who are living these experiences, and we hope to provide enough information that they’re less alone and better resourced about their needs.

Keep up with Kathryn at thelonestardiva.com and @thelonestardiva on social media. For more information about Trans+: Love, Sex, Romance, and Being You, visit thetransbook.com and @thetransbook on social media.

[…] Profiles in Pride. (2019, December 9). Kathryn Gonzales: On overcoming the trans narrative and making the world better for LGBTQIA+ youth. https://profilesinpride.com/kathryn-gonzales-making-world-better-for-lgbtqia-youth/ […]