In 1976, Larry “Lare” Nelson, a native of Minnesota, went to San Francisco for what was supposed to just be a month. He had been accepted in the Peace Corps and decided to spend a few weeks living it up in San Francisco before starting his assignment. But after falling in love with the city — and a man — he decided to stay put, and he officially relocated there in the fall of 1976.

Nelson took a professional job working in the Financial District, but in his free time, he enjoyed the fun and debauchery of the gay bar scene. Then, when he was 28, the AIDS crisis hit and he watched his friends die, and it changed his life forever.

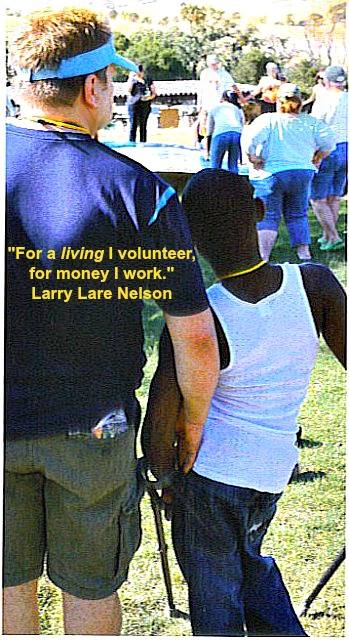

Nelson’s mother had always been an active volunteer, and watching so many of his friends succumb to AIDS drove Nelson to become incredibly involved in his community. Volunteering became his greatest passion, and he’s helped countless organizations, such as the AIDS Life Cycle, where he’s been involved in various capacities for 21 years, and Camp Sunburst, a camp for children infected with or affected by HIV, where he served as a volunteer camp counselor for 15 years (you can see his full list of accomplishments on his Facebook page). The recently-retired 65-year-old now treats activism and volunteering like a full-time job.

“For two and half decades, I have been the one getting up early, loading and unloading supplies, garnering volunteers and fundraising,” he says. “I have not been the one with the microphone or bullhorn. I think that is changing.”

In addition to being an active volunteer in a variety of causes, Nelson is the author of San Francisco Pride’s 2018 theme, “Generations of Strength.” He’s also working to set up an intergenerational tent at the festival, which would give young queer people the opportunity to learn from older ones.

This is Nelson’s story of living through the AIDS pandemic, developing a passion for volunteering, and coming up with a theme for one of the nation’s largest Pride festivals.

Profiles in Pride: When did you come out as gay, and what was that process like for you?

Larry “Lare” Nelson: My first sexual experience with another male was my neighbor when we were young men. We had an affair for around four years, and I was so sad when he moved. I didn’t know what that was; I didn’t really know what sex or sexuality was, we just thought it was fun. I never considered it experimenting.

I never thought I was different until someone told me I was different. My being gay has always felt very normal to me. I really have never cared what other people thought. However, I had a girlfriend in high school and in college, because I was raised in Northern Minnesota, and we had to put on a front.

In college, I was in student government, and I was a big man on campus. My college girlfriend was in speech and theater, and I did some speech and theater — well there’s a big surprise! I went to college in North Minnesota, and there was a bridge to Superior, Wisconsin, like the one from Oakland to San Francisco. There was a gay bar in Superior, Wisconsin, and my college girlfriend took me there. It was very secretive. It was also very exciting in those days when we were secret; I know it sounds odd, but there was some excitement about sneaking around. She brought me to this bar, and I said, “What are we doing here?” She said, “You are so gay!”

In college, I told everyone I was bisexual, because I thought that was safer than telling people I was a gay male. But then again, it never mattered to me that much. That was the only thing where I think I was hiding in the closet. But I was still having encounters with men, not so much with women. You know, my girlfriend was like a buddy, and I had to do the obligatory “guy stuff.”

I think when I really came to grips with it was we drove down from Duluth to Minneapolis on a weekend, and we had to park five blocks away and walk down a dark alley and knock on some door, and we were let into a gay bar. It was exciting and titillating, but in retrospect kinda weird, like a speakeasy for gays! Then I started coming out more and more, and by the time I finished college, everyone knew I was gay. Nobody cared.

PIP: When did you move to San Francisco?

LLN: I was going to go in the Peace Corps after college; I was accepted. I decided I was going to go to San Francisco and party down for a month before I went off on this adventure. I met a guy and fell in love with him. I never went to the Peace Corps and I moved out here two months later in fall of ‘76. I moved out here fresh, 23, skinny, and with Farrah Fawcett hair.

The first few years I lived here, it was really all about going to bars and drinking and dancing and meeting men. That’s what you do in your twenties! I’ve found that when a queer or bisexual person comes out, there’s an adolescent period. For example, in the straight world, you have a group of friends to hang out with and then you pair off with someone. In the gay world — I use “gay” more than I use “queer,” but I use them interchangeably — in the gay male world, that group dating thing is the bar. Then you pair off.

The bars were also where you met people. There were social and political organizations, but those were for the “boring” people. So basically, at least in San Francisco in my experience, in the mid ‘70s to early ‘80s, the social gathering spots were the bars. Then AIDS hit, first known as GRID. We were like, what the hell is this? Then there were organizations and clubs that popped up.

I had also continued to build a career; I was a suit in downtown San Francisco in the Financial District working at primarily a bank doing mergers and acquisitions. I had a successful career and continued to do that.

But I’ve always been radical in my thinking; I had been an activist in my mind, but it was really 25 years ago I started acting upon it after seeing the devastation of what we know now as the pandemic of AIDS.

PIP: I’ve read interviews where you talked about what a toll the AIDS crisis took on you and the community in every way. How did that experience impact you and shape who you are today?

LLN: The impact, wow. It still impacts me. I’m 65 years old, and over half of my life I’ve been thinking about AIDS and the HIV virus. And what wasn’t done the first 10 years, and how much further along we could possibly be now if something was done by my very own government, who ignored us. Because the two most loathed groups of people at the beginning of the AIDS crisis were gay men and black men, so we were just ignored. Just think about how much further along we’d be if 10 years hadn’t elapsed before anyone did anything.

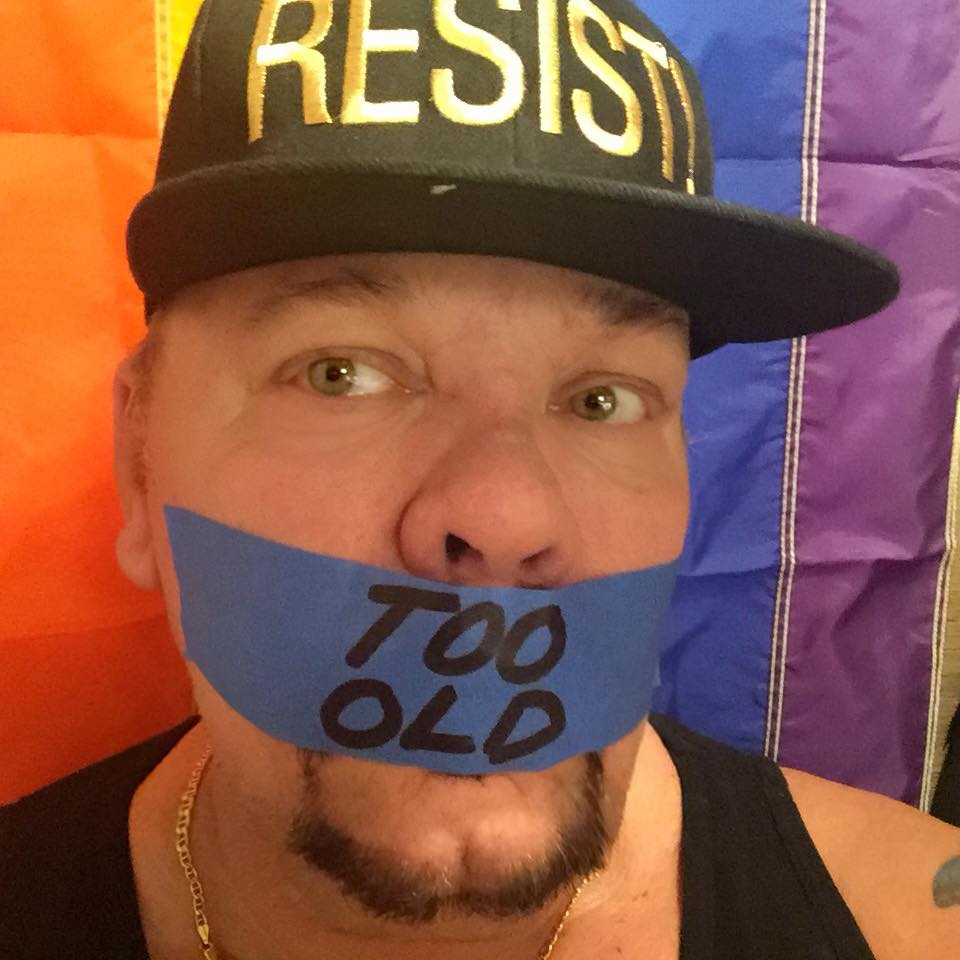

As far as it affecting me on a personal level, I’m often asked this question by young people, who I love. I love young queer people with their hair, their clothes, their gauges, their piercings, their tats, whatever. Every time I see a young queer person in their teens or twenties, I look at them and I think, “Thank God they look different, because that tells me they’re alive — that they did not feel that they had to kill themselves.” Someone else may say, “Look at that hair! Look at those gauges!” I say, “Look at them, they’re queer young people, they’re really proud of who they are.” I think that is wonderful.

But back to AIDS: young people often ask me, “What was it like before AIDS?” I tell them very explicitly what the sexual encounters were like; what we did. It was really wild abandon here in San Francisco for quite some time. It was on the heels of the sexual revolution, right? So I tell them about what it was like sexually — not using condoms, how fabulous it was and everything.

Then they say, “What was it like when AIDS hit?” I tell them, “Imagine you had a birthday party right now, and you invited all of your really good friends. You’d have 10, 20 people over, right?” They say yes. I say, “Imagine that group of people over a period of two years, gone. That’s what the AIDS pandemic was like. So if that doesn’t fuck you up, nothing will.” I spent four years in weekly therapy.

For the AIDS Life Cycle, I’m coming up on my first 21st consecutive year. I was a cyclist for nine years, then a roadie for 10, and a virtual cyclist last year. I was done, but I’m going back this year because it’s the 25th anniversary of the ride, and a lot of the veterans are going back. But this really is my last year on the ride as a roadie.

There’s an irony here — think about this. The healthiest I ever was in my life was when I was training to be a cyclist in AIDS Life Cycle. The most unhealthy aspect of my community causing people to die made me the healthiest I ever was. Isn’t that crazy? Because we’re training; you can’t just get on a bike and ride to L.A. for seven days. You have to train for six months, every single weekend or any days you call in sick to just go train. It hit me at the time; I said, “My God, Larry, do you realize you’re the healthiest you’ve ever been and it’s because of your friends being compromised health-wise and dying?” That’s kind of nutty. It’s such a juxtaposition.

You know, there are many of us who had and still have this thing called “fuck fear.” You just didn’t have sex. A lot of bars closed, people didn’t go out. It was very dreary. In fact, there were six years in a row where at the Pride parade, it was raining. It was just so dark and awful in the city and so depressing. I remember so vividly the one Pride year when the sun came out, and it was just like, “Oh my God, maybe things are going to change now.”

AIDS has been a huge part of my life, and I’ll tell you, even though I’m not physically impacted with the virus or diagnosed with AIDS, my generation — the part of the “lost generation,” which is still alive, meaning people like me — we have PTSD from surviving and going through the AIDS pandemic.

What I’ve been talking about along with this “Generations of Strength” theme I’ve created for San Francisco Pride this year is the need for really good and true mental health care for senior citizens in this generation of mine that have gone through and come out the other end, so to speak, of this AIDS pandemic. So I made it a concerted effort — I said, “Larry, you can do something.” That’s the whole other part of the story, is how the role model for me and my volunteerism and activism and philanthropic work was created at a very early age. As far as AIDS pandemic, it was a huge impact; it completely changed the direction of my life.

PIP: Speaking of volunteerism and activism, what motivates you to be so involved?

LLN: There are those of us in my generation who feel that we have a responsibility to represent those who are gone who aren’t here to volunteer and carry forward our history.

I’ll also praise my mother for setting the model for me as a child and as an adult. Mom would repeatedly tell my brother and I that all people from babies to seniors need help. That was the beginning of my activism — my mother. Us gay guys, most of us have really great relationships with our mothers. They’re queens to us, but then there are some that don’t have any relationship. So I consider myself very fortunate.

But I asked my mother why she volunteered so much. She was a den mother for 20 years, and she was a senior activist later in her life. Earlier when she was a den mother and she was volunteering at church or scouting or whatever she was doing, I said, “Mommy, why do you volunteer so much?” She looked at me and said it was her way of repaying society for us being on welfare and living in public housing.

There’s a tie-in here. I can tell you that this is the same model I’ve lived with my entire life. With respect to San Francisco, it’s like for decades I’ve been giving back to the community that likely saved my life by offering a safe and queer space for me to live my life in. So that role model of her saying, “I’m paying society back” is how I’ve always viewed my life, and exponentially over the past two-and-a-half decades of how I view living in San Francisco, because it saved my life. And I have so many friends who died.

I don’t think my mom realized that she was creating an activist, but I think, knowing my mother, maybe she did.

PIP: What are some of the causes you volunteer with that are most important to you?

LLN: I think my volunteer work is really activism, because when I think of an activist, it’s someone who gets out there and does things and talks about things, and that’s what I’ve been doing so long. I would call it volunteer work, and then I’m thinking, “I’m an activist, dammit.”

All of my work is skewed toward AIDS organizations, but as I said, my mom told me everybody needs help, from babies to seniors, so I try to mix it up. I’d say my top favorite things, or most prolific things I’ve done, are of course AIDS Life Cycle for 21 years. I also ran a gay senior men’s potluck for four years.

I also created a not-for-profit of my own, where I collected cycling clothing from cycling clothing manufacturers because that gear is expensive. The jerseys are $100, and the shorts are $100. I ran it for 15 years and gave away free jerseys and shorts to brand new AIDS Life Cycle participants. I stopped because I got sick of having boxes stacked up in my house. Then I worked for a long time with both Komen and AVON breast cancer walks. That has been wonderful.

So it’s skewed toward AIDS, but I’ve tried to mix it up and have a variety. One of the things I’m most proud of is I was a camp counselor for 15 years at a summer camp, Camp Sunburst, for 6- to 11-year-old kids infected with or affected by HIV/AIDS. I had to step away from it, but they’ve had a huge impact on me. I loved the kids. My fellow co-counselor, we were together 12 of the 15 years, so we graduated three groups of boys from camp. I’m really proud of that and did a really great job, and they had a huge impact on me.

Also, this is my second year to be a reading tutor for fourth graders. There’s a lot of stuff on my list, but those are the big ones.

PIP: Your idea of “Generations of Strength” was chosen as this year’s San Francisco Pride theme; how was it selected?

LLN: With any gay organization, or for that matter, any non profit, it can be rather political. I’ve been a member of San Francisco Pride for some time, but I only ever go to annual meetings to vote the board of directors in. I wish to be more involved now that I have the time and interest.

Prior to the annual meeting, they sent out an email blast asking for submissions for a Pride theme name. I put in four or five of them. They were up on a wall in the meeting room. I want to say there were 70 themes taped up on the wall and all the members got some colored dots, and they could use their dots to put them on the ones they liked best. They narrowed it down from 70 to 10, and then down to one, and mine was chosen!

In addition to creating one of the themes, I was also one of the official nominees for grand marshal, but I didn’t get it. They had 60 submissions, but I made the top 10 at the member meeting. It’s my first year being nominated, and again, heavy lifting. But as my best friend told me, she said, “That’s OK, boo, you know why? Because they’re coming to the party you named!”

PIP: So true! How did you come up with “Generations of Strength”?

LLN: I was sitting here in my recliner watching something about the holocaust. I remembered that suspected lesbians and gay people were the first to be picked up and tagged and imprisoned and experimented on and killed and gassed and every other thing that happened during the holocaust.

I thought to myself, “God, for generations we’ve had to be strong. We’ve had to have strength. Oh my God, that’s my theme! Generations of strength!” That’s why I submitted it. It’s receiving huge press so far!

PIP: I know you feel passionately about queer youth knowing the community’s history and having mentors and role models. Why is this so important to you?

LLN: Because I want them to stay alive. I want them to be able to tell future generations that they can survive. And here’s the deal, this is part of the generations thing: When I was thinking “generations of strength,” I was thinking older people, but someone pointed out if it’s generations, it’s everyone.

When us senior people start talking to these kids and they ask us questions, they see that we survived. But they don’t know how we survived, so we have to let them know how to survive.

But here’s the rub: sometimes we don’t even know how we survived until we start talking about it. We know we survived. And someone asks you, “How did you survive?” I don’t think any person can just say, “Well, I did this and I did that.” You say, “Geez, I’ve gotta think about that, how did I survive?” I think it’s critical to the overall well being of the queer community and across generations.

This communication is important because as I said, I want young people to stay alive and be proud of their history. The GLBTQ+ community has such a deep and rich history. It really is amazing how we have survived. I think the information that has come out in the last five years about fluidity and all of that — I don’t think that would have happened without the gay movement. And I don’t think the gay movement would have happened without the civil rights movement. It’s all so connected and has been through generations; I think it’s a natural progression. I think it’s so important to have these intergenerational communications.

What I’m bucking for this year, and I am getting more people on board — I want a canopy with tent and chairs at San Francisco Pride Festival for an intergenerational communications tent. Even if I have to pay for it myself, I’m going to get the canopy and chairs there. I’d like to call it “Seniors Tell All,” something like that; I’m not sure yet. I was going to say “Ask a Queen,” but that’s not inclusive.

I already have senior citizens aged 60 to 80 that would sit there. Young people can come and ask us any question they want to ask — any question whatsoever, about sex, what was it like, what do we do. See, when that happens, this goes back to what I said; they see we survived. They’re right there with us looking at us. They ask us, “How do you get through all this?” Maybe we haven’t thought about it before. We start talking about it and we realize it, and that’s when all the pearls of wisdom come out. I can’t emphasize enough how much I just love the young queer community. Not only are they adorable, but they’re just open and active, and they’re just fantastic.

You see, when I go away my story should not go away, and it’s so critical that our youth know our history and have real-time role models and mentors.

PIP: How does your volunteering benefit you personally?

LLN: Among a bunch of my friends, I’m known as Mr. Noncommittal. I was in a relationship with a guy for eight years, and I’ve had boyfriends through the years, you know, but I’ve just kind of settled into this thing where I just can’t be bothered. You hit 50 and it’s like, OK I’ve gone through enough shit, I’m done! Maybe a little “date” now and then, but I get my love from volunteer work.

That’s kind of skewed and that’s kind of weird. Some people say, “Yeah, but you need a man.” I don’t; I really feel that I get my love and my hugs from my volunteer work. Yeah, it would be nice to have a partner to share things with, but I don’t, so what am I going to do? Sit at home and lament? No! I’m going to continue with my volunteer work. I really feel that I get so much love from volunteering. It’s like they say, I get way more than I put in.

PIP: Is there anything else about your life you’d like to share?

LLN: I think it’s important for the community to know that I feel the greatest blessing in my life is having grown up poor. It taught me that there were others like me and my situation can change and I can help others. That’s the same concept I’m thinking about when it comes to a sharing stories of survival and sharing our stories through generations.

Because like my growing up poor teaching me there were others like me, it’s the same thing with these intergenerational communications. Queers teaching queers. And queers teaching non-queers. Parents, so they can understand their kids. Then they realize, “Hey, I can change this! I can change whatever it is! I can change the way I view myself! I can change the way people view me! And in that process, I can help other people.”

My other great blessing was having a strong role model. My mother raised two boys on her own in a project on welfare and she was amazing, and she volunteered. I guess my mother was an overdoer and she didn’t know it. That’s the same model I’ve lived my life by.

PIP: It sounds like you’ve been through a lot, but you’ve used what you’ve gone through to create so much good in the world!

LLN: I’m a true “trials and tribulation coming out on the other end” story. I have depression; I think everybody does to some degree. But I just remembered my first year at summer camp, which was right after I finished that four years after therapy dealing with loss of friends from to the AIDS pandemic.

To be honest with you, I didn’t know if I was going to come out of that. At the beginning, I didn’t tell my therapist, but I told myself, “If I come out the other end of this, I’m gonna tell everyone how I came out of it.” So that first year at summer camp, we had to sit in a circle and talk, and I told my story. I said, “You know what, I went to therapy because figured if I was carrying that grief, I would not be an effective camp counselor for these kids infected with or affected by HIV or AIDS. I finished that therapy yesterday on a Friday, I’m here at camp on Saturday, I did that work and I’m ready.”

One other thing I want to get across: you’ve probably heard of Taylor Made products, the scales and golf clubs. They’re in the Bay Area and they’re the ones who built the infrastructure for the summer camp I volunteer at. The husband Barry Taylor died a few years ago, and I went to the service.

One of his kids got up there and said something about him that I have adapted, and it’s basically how I want to be remembered. I thought it was so lovely what she said. It goes like this: “He lived his life as a prayer.”

I just love that. You can pray to anything: God, Buddha, even Oprah! A prayer can be anything. Prayers to me are maybe different what prayers are to you, and it doesn’t have to be religious. But isn’t that nice? “He lived his life as a prayer.”

In the meantime, I plan to devote the next decade and beyond to ensuring that LGBTQ+ seniors have increased visibility in our community, are not discriminated against in employment or the receiving of services, and are involved in the overall decision-making on matters that affect our community and in helping prepare our youth for their later years.

More important than about me, but back to where we started in this conversation: I want someone, somewhere to read this and say, “Wow, he grew up poor, he lost most of his friends, he’s OK, and has kept the strength to volunteer.”